We are still fighting Filipinos

Who was dispatched to the Philippines instructed to "Get at the rock-bottom facts of the situation in the islands and report without fear or favor or prejudice." The result will be seen in two articles published in Collier's Weekly, of which this is the first.

THEY SLEEP WELL in Balyan. The little transport had blown its whistle for two long hours and yet not a sign of awakening came from the mysterious garrison lost in the jungle. Red:skirted women, 'carrying baskets of fish upon their shapely, well-poised heads, paced in single tile along the beach, merely a silver barrier between the green sea of foliage beyond and the blue, pellucid waters upon which we rose and fell. From out of the concealed opening of the river now and again a heavily laden native boat would appear only to disappear again from view behind the fringe of bamboos and cocoanut trees where we suspected the town of Balyan to be. The quartermaster's clerk, a human wreck if I have ever seen one, barked and coughed in a way which almost made our little craft quiver. It certainly did me; but he talked quite cheerfully. “The doctor in Manila had advised him to go home and see his folks, and then, of course, everything would be all right.“'I know that type,' said the pessimistic pilot, a Filipino, "and why shouldn't I? I have seen so many. He will only last the time it takes to smoke three cigarillos.”

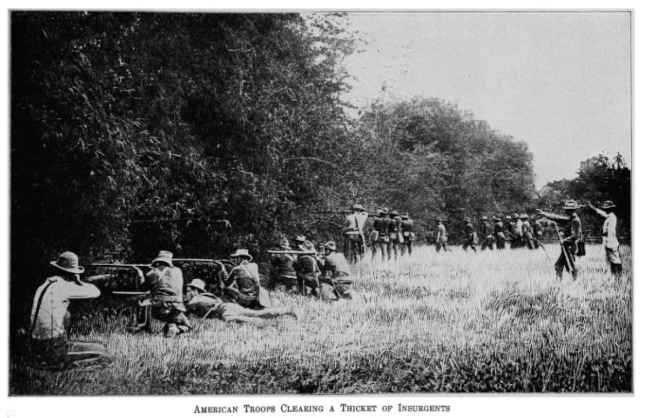

Finally a sergeant came out on the beach with three or four heavily armed men, who seemed by the way they clutched their rifles to expect a cavalry charge at almost any moment, and wigwagged that he could do no business with the Custer to-day. "There is a big fight on,” he flagged, “and we can't spare a man.” So with a snort of indignation the Custer proceeded on its journey over the transparent seas and along the sunlit shore.

Taal we next aroused. It was hard to leave the great convent and church that crowned the heights here like some cathedral fortress of old Spain all unexplored, but they gave us quick despatch in Taal, both passengers and freight were waiting our coming in native boats anchored far out in the offing.

AWAY FROM WHERE DEATH LURKS

Among the passengers was an army lady who shuddered and smiled with the memory of her recent experiences as though she had chills and fever. It is not much of a place, Taal, but it had been paradise to her. The night before her husband had been ordered out on an expedition and she back to Manila by the commanding general, who directed that no women should be allowed to live at the army posts in Batangas until further notice, She took everybody into her confidence, and told us of the steady tread of the men, as they marched out in the darkness past the convent windows with her husbund in the lead.

“And then you asked me to. play 'hearts', captain.”

The captain who was seeing her off acknowledged with a blush that this had been his suggestion.

“Oh, I wasn't afraid,” continued the little woman: “and I wasn't nervous a bit, but I couldn't play 'hearts'. I could only hear their steady tread and listen for the return.”

We steamed on now across the bay, making for a promontory and, in the dazzling sunlight, a head-on collision with it seemed inevitable; but the captain picked up a little rift in the mountain-side and we slipped out of the broad sea into a little strait so narrow that the overhanging trees brushed our awnings. When we came out again into the great water there was a merciful veil of clouds overhead. The brilliant bay looked leaden. Half a dozen waterspouts were moving over its surface in the most alarming manner, and almost before we knew it the sun was setting behind Mindoro and there before us was Batangas. No great shakes to look at, especially when as now everybody was assembled at the other end of town to hear the news of the big fight that had come off in Bauan that morning.

It was a great fight, and mighty glad I was to hear of it: still patriotism has its limits, and I hated, as a consequence of this military success, to be compelled to walk up the main street of Batangas with my trunk under one arm and my saddle under the other, It was hard, also, to miss the best fight of the year when, after all, if it had not been for the hard sleepers in Balyan, we might have arrived in time.

It seems that four hundred insurgents, one hundred riflemen and three hundred with bolos, lay in ambush on the Taal road waiting to bushwhack the army train. Word had reached our people, no matter how, of what was in the air, and Captain Hartmann of the First Cavalry rode out with his troop to punish their impudence while Mrs. Hartmann watched proceedings from the church tower. "I knew, of course, Jerry would win,” she ,said, “and I didn't think he would get. hit, but. oh! how splendid it was. They never stood their ground a moment, and we would have gotten them all, Jerry says, if each man. hadn't run in a different direction.”

But it was good enough as it was, though the army ladies of Batangas evidently thought Mrs, Hartmann should have invited them to her coign of vantage in the Bauan church tower. Still it is not given every woman to remember her social duties when her husband is under fire, and perhaps the fight was not big enough to let those headquarters ladies in, too.

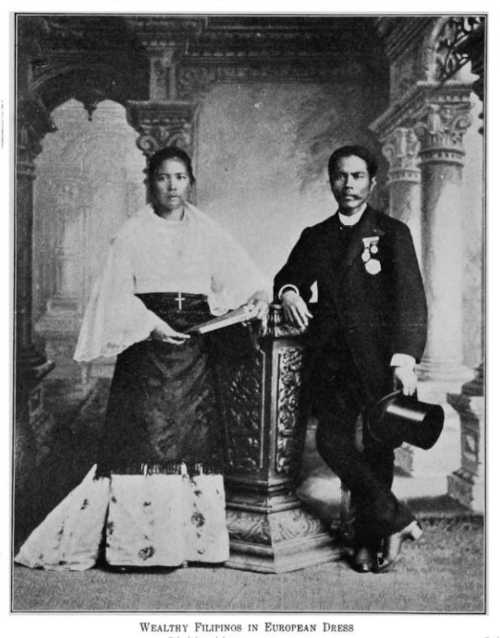

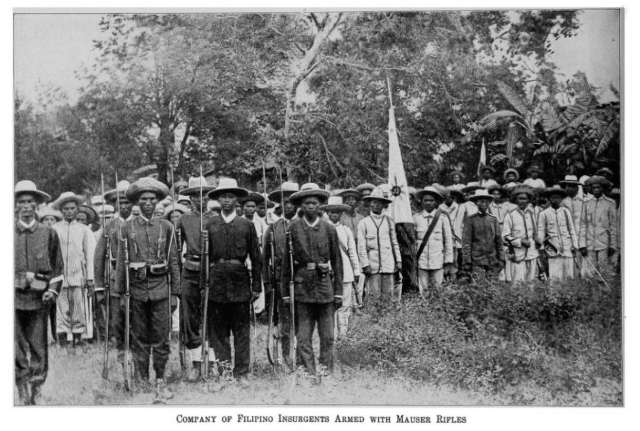

HOW INSURGENTS CARRY ON WAR

Only one of our men wounded, and just as I appear on the scene with my trunk and my saddle the doctor rides in with the glad news that he will probably pull through, Among the thirty or forty dead the insurgents left upon the field there was a man with a strangely familiar face whom everybody recogmized but no one could name, He wore amigo clothes and they carried him on a litter two miles back to Bauan, where he was recognized as one of the leading men of the place, a merchant worth several hundred thousand dollars. He was such a friend of the Americans that he had been allowed considerable liberty. Only a week before he had gone to Manila on business, as he protested, but, as it now appeared, to see the secret Junta, and was carrying information to the insurgents in the field when fortunately Hartmann struck the band. This little incident, to my mind, sheds more light on the methods and the means by which the insurgents carry on the war than all the official folios and voluminous reports that have been published.

That was a busy night in Batangas. General Sumner sat in the telegraph office until midnight sending and receiving despatches which showed that Malvar was on the move. The only unsatisfactory feature of the situation was that he seemed to be moving in every direction at once. I had hardly shaken hands with Fassett, just back from his daring march through Mindoro, when the general sent him off, and he disappeared in the bush with his men behind him just as he used to do in Cuba, At ten o'clock insurgent fires were lighted on the mountains behind the town and Roman candles were sent up as signals from mountain-top to mountain-top. I rather thought the insurgents were taking note of my arrival, they having shot up the town only six weeks before in honor of Judge Taft and his civil government, but soon the wires brought in news that similar fireworks were being displayed at Taal, Lipa, and San Jose, Whatever else it was, candor compels me to say that it was not a personal tribute. The general sends out detachment after detachment through the night, and at last, when day is dawning, something definite as to the insurgent concentration is ascertained and young Heinzelman with half his troop starts out across the country to San Pablo with information that cannot be intrusted to the wire, and welcome orders for Colonel Wint to move.

This was simply the beginning and, as far as results are concerned, the end of a week—November 11 to 18—of feverish activity on the part of our men in Batangas Province. The information which influenced our movements was not wholly inaccurate, We always came to where the insurgents had been but never to where they were, and at the end of it all there was only the spectacle of the used-up men and horses to show for our pains. I have always had a proper respect for the army mule, but when I remember what he represents, when placed in the Batangas field, to the taxpayer and to posterity (about $800 gold) my respect deepens almost to veneration.

“WHAT WILL CONGRESS DO?”

I spent the morning of my first day in Batangas talking with the presidente and the provincial secretary, having been instructed by high authority to draw for their edification (and for circulation in the province) a lurid picture of the stern phase of war I had seen in Samar which might, under the spur of necessity, be repeated in Batangas. They listened with evident interest at first, but that soon passed, and they, too, as every other Filipino of the more educated class I have met, began to question me about Congress and what Congress was going to do for them. "Will they do what the Federal party has requested?” (They were both Federales.) “Will Congress convert the islands into an organized or an unorganized Territory?”>

I had the utmost difficulty in proving to them that I did not know what Congress would do, that perhaps even Congress didn't know. It is very exasperating to have to be continually explaining our system of government to the Filipinos, and they never can quite understand how our constitutional aversion to making up our minds about anything we can let slide for a few months longer is at once our boast and the palladium of our liberties. This conversation left on my mind a very decided impression that these two civil officials were very much dissatisfied with conditions and only deterred by fear and laziness from taking the fleld against us in person. It was apparent, as on so many previous occasions, that these men regarded our vague promises or our sinister silence with more apprehension than any definite scheme of government could inspire, however small their promised part in it might be.

On the following morning I set out upon my ride across Malvar's country with an escort of the bay troop of the First Cavalry. From Lipa I went on with a corporal and ten men of the grays, and five days later a bodyguard of the chestnut troop brought me to Calamba and Lake Bay. The day of our departure was market-day in Batangas, and for three or four miles out the road was thronged with men, women and children dressed in their best and all carrying baskets of fruit and vegetables to be exchanged for a few centavos or the rice and decayed fish upon which they exist. The first hours of our ride were very uneventful and as the misty rain concealed from us in a great measure the beautiful tropical scenery through which we passed I was ouly too glad to welcome a diversion of any kind, and about half-way to San José, a military post and our first halt, one did present itself. Suddenly the still valley through which we were riding was filled with a mournful chant. Immediately our point halted.and held a consultation.

“I guess it's one of those dios-dios men getting the people together for a sing-song. A new kind of religious sect starts up every day in Batangas, and Malvar is behind all of them. We must get at the bottom of this and run them down,” said the corporal. So, dismounting, we left our horses and climbed the hillside. On the little plateau at the top, almost hidden by the bamboos and the rank, tall grasses, we make out a great nipa shack from which the dolorous, far-carrying chant came. Surrounding the place, we all rushed in. A dried-up little old man with a red kerchief round his head and great horn-rimmed goggles over his eyes was teaching in this bush school a few score waifs of the jungle, probably all children of Malvar's men. It was some minutes before we could induce teacher and scholars to emerge from under the bamboo benches where they had taken refuge in abject terror at the sight of the soldiers.

“What do:you teach here?” I inquired when some order was restored.

“Doctrina,” said the little old man. And very good, humble doctrine it was, for before we started on we persuaded the children to resume their chant and we were followed by the refrain from scores of childish throats: “'Yo, pecador, me confieso.” (I, a sinner, do confess myself.)

“BAD BUSINESS” AT BATANGAS

Why Lipa should be insurgent it is difficult to say, but it is nevertheless true. Its inhabitants belong to the educated moneyed class to whom our stable programme should appeal, and yet they favor Malvar.

Stephen Bonsal

When we rode into San José we thought at first that this substantial town had been burned away, but it was not so bad as that. Only about thirty houses had been destroyed, and the commanding officer, with his arm in a sling as a result of the fight, told me how it had happened. In the night, only a week bagan the insurgents had secreted themselves in these houses to capture a valuable train which was daily expected from Batangas. Lieutenant Connolly of the Twenty first Infantry was impatiently expecting the train also —it was bringing much-needed ammunition— and so he strolled out to the edge of the town quite alone to meet it. The secreted insurgents could not resist the temptation and let him have a volley, only one shot of which took effect. The train came up at about this moment and a lively fight ensued, in which all the nipa houses of this end of town were set on fire and quite a number of insurgents killed. . Like so many of these little affairs, however, it was of small consequence and without result. I think the sergeant who showed me over the field rather hit the nail on the head when he summed up the whole situation in Batangas as a bad business, “We must get into close quarters,” he said, “or get out. This thing of killing a few taos (country louts) every week isn't going to settle anything. The fact is, we are not hurting them a little bit and they are hurting us a whole lot and they know it."

The people of wealth and education, and there is still much of both throughout the province, seem to prefer the experiment of a Malay republic to the assured stability of American government, It is incomprehensible, but nevertheless true.

We went around the "dead man's gulch", where many an army train has been attacked, and by a circuitous forest path an hour or two later rode into Lipa, almost intoxicated with the fragrance of the orange blossoms so overpowering at dusk. War and the coffee worm have done their worst with Lipa. The wealth and the prestige of El Tiempo de Cafe, the coffee days, have fled, only the magnificent stately houses and to some extent the culture of its inhabitants remain. Why Lipa should be insurgent it is difficult to say, but it is nevertheless true. Its inhabitants belong to the educated moneyed class to whom our stable programme should appeal, and yet they favor Malvar to a man. I met a very charming lady here, one of the gente fina whose jewels to the value of $80,000 had been confiscated by the insurgents during Aguinaldo's regimé and placed in the war chest, yet she had not a word of blame for them and took little or no pains to conceal where her sympathies were. Here we have one of the few facts of the situation that cannot be disputed. The people of wealth and education ,and there is still much of both throughout the province, seem to prefer the experiment of a Malay republic to the assured stability of American government, It is incomprehensible, but nevertheless true, It was curious to meet that evening in the casino half a dozen men at least who had studied in the universities of Berlin, Madrid, and Paris, who, with all their culture and education, could find nothing better to do than to play monte for five or six hours at a sitting with the chinos, the half-breeds and all the other queer people who make up the membership of this very mixed club, On the other side of the casino the leading ladies of the town also gambled long and patiently to the smoking of many cigarettes, playing panguingue, a doleful game, at which you cannot lose much more than a peseta an evening. Outside the ladies' gambling parlor, stretched upon their straw mats, lay sleeping the maid servants, with their lamps lighted, waiting patiently often till near morning for their mistresses to come and bid them light them home.

“BRIGADIER” FELIPE MOLOLOS, BANDIT

The next afternoon, as we lounged about the club in Lipa rumors came in that something bad happened to Captain Felipe Mololos of the insurgent army. What it was we could not make out at first, but Lieutenant X——, who lounged with me, was all attention in a moment. He took an especial interest in Felipe Mololos. Felipe was his "private pigeon", as it were, He felt as if he knew him, though he had never seen him, worse luck, in a hike of a month in the Lobo Mountains. As quickly as we could shake off the siesta feeling we got on our horses and started down the sunny road toward the barrio from whence the news had come.

“He is one of the most active men out,” said the lieutenant as we galloped along. "He and his men can outhike old Nick himself", as my poor fellows, you will find most of them in the hospital, can testify. Felipe was a bit of a brigand and a good deal of a ladrone, but he has become one of Malvar's most trusted men. I'll tell you how he got his captaincy. It was rather neat. Malvar issued an edict announcing that hereafter any man who presented himself at headquarters with twenty-six rifles should be given the rank of captain. Felipe's arsenal was a little short of the required number, but he burned to be a captain and wear shoulderstraps, and so he invited Juan Martinez, another local chieftain, to celebrate a war-talk with him and eat some carabao steaks. When Martinez's men were gorged with carabao, Felipe fell upon them, killed a number outright, disarmed the rest, secured the needed rifles and became a captain in the army of Liberty. There are no flies on Felipe. If he were in the United States Army he would be a brigadier in a month,

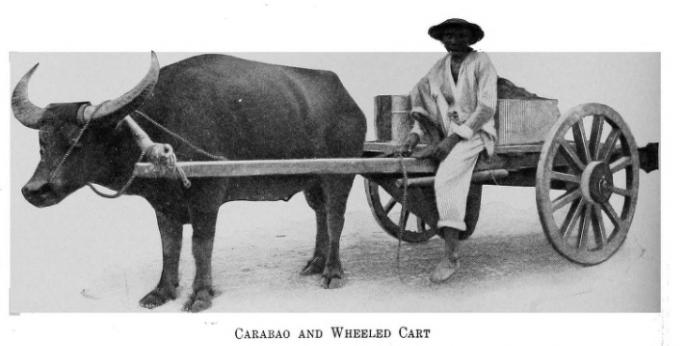

A few minutes later we met a cart, a bull cart, coming along the road at the rate of half a mile an hour. It wus half filled with loose bundles of zacarte grass clotted with blood. Under the bundles we could see the outline of a human figure. “It's Mololos," said the lieutenant.

Beside the bull-cart driver sat a rather good-looking young woman, calm and expressionless. The bull-cart driver said he didn't know anything. On cross-examination he asserted that he had sworn upon the Holy Cross to say he knew nothing. Could any Christian question him further? Strange men had come to him, men he had never seen before, had placed a man bleeding from numberless bolo wounds in his cart and had then gone away. He was driving in to Lipa with the wounded man because the doctor might heal the wounds and the commandante might give him a peseta.

Then we gave the bull-cart driver up and tried to be patient like the silent woman who sat beside him, every now and then brushing away with a wisp of zacarte the flies that lighted upon the livid face of the man who was bleeding white. Soon we came to a stream, and the bull-cart man unharnessed his beast. "My carabao will die of heat apoplexy if I press on”, he said. We had come a mile and a half in two hours. His wallow of half an hour in the mud and water did the carabao a lot of good. He swelled visibly before our very eyes. He had grown so big that we had the greatest difficulty getting him back into the shafts. When the bull-cart man had taken out a can of oil and anointed the animal's shining skin we pressed on. Revived, rejuvenated, the carabao now made as much as a mile an hour.

A SCENE OF BLOOD AND ANGUISH

It was dusk when our little caravan, to which every idler we met joined himself, reached army headquarters. The doctor was waiting at the door. Soon Felipe Mololos was on the operating table, the coverlet of straw withdrawn and twenty-seven gaping bolo wounds revealed. And then suddenly the silent woman found voice and told her story, the best story she could tell for her man. Felipe was coming in to present himself, she said. For some time past he had been disgusted with Malvar and more and more attracted by the government of the Americans. Very foolishly, and much against her will, he had said as much to other insurgents, and invited them to go in and pay their homage to the good Colonel Americano. They had lain in wait for him and cut him up in consequence, Then the woman, bursting into tears and curses, brandished her little dagger, which she smeared in the blood of her man, and called upon the sacred images that looked down upon the scene from the convento wall to witness her savage oath, which I shall not reproduce here.

There was no doubt about Felipe having been cut-up. There was not an ounce of blood left in his body. The dark-red man had turned a dirty white, The doctor and the hospital men had sewn up wounds aggregating in length five yards and a half and there were others sull gaping when suddenly Felipe died.

It was about this time that the teniente of the barrio came in to tell his yarn. The moment his voice was heard the woman who had watched the surgeon sewing with a kind of detached interest sprang to her feet with a feline shriek and it took four soldiers, and good stout ones at that, to restrain her from sheathing her dirk in the teniente's heart. When the woman had been removed, the teniente went on with his story, It is wonderful how eye-witnesses disagree. Felipe had come to town, asserted the teniente, and demanded a carabao. This was of course immediately given him, but he then demanded another, a pet one, the favorite of the village. “I told him that I could not do this without the consent of the principales, the chief men, and I hastened away to get this. They also were averse to giving up our pet, so we returned to the shack where Felipe was resting and drinking vino, and told him we had come in a body to pay our respects and to ask permission to gaze upon his bolo with which he had accomplished such daring things. He seemed pleased at this, gave us the bolo, and then we cut him up.”

“Where is the man who pays me the peseta?” said the bull-cart man, And then we all went to supper.

THE SITUATION IN MALVAR'S COUNTRY

A word about the military situation in Malvar's country, On the spot it is perfectly obvious, the facts plain-spoken and undeniable, but somehow or other everything looks different in Manila, less than a hundred miles away, and | cannot help thinking that there something, perhaps politics, exercises an obscuring influence. Malvar can place in the field any time he wants to between four and five thousand men. I state this figure because it is the lowest I have heard mentioned by conservative observers. Of these at least two thousand are armed with rifles. I think myself that Malvar disposes of a great many more rifles than this, but again I prefer to use the lowest figures obtainable from the most conservative sources. There are still fourteen or fifteen thousand rifles unaccounted for in the island of Luzon, and I do not believe, if the insurgents needed more, they would have any appreciable difficulty in getting them, And they should have no difficulty in getting new rifles even if they are without money, and there is every reason to believe that they are fairly well provided with funds, because we pay thirty Mexican dollars for any old rifle they turn in, With that sum in Hong Kong your insurgent can get the best rifle that is made, The navies of Spain and the United States combined could not blockade Cuba and of all the smuggling expeditions that sailed in only one was captured, There is much reason to believe, then, that our Asiatic fleet, or even the whole American navy, could not effectually blockade Luzon, and that the insurgents will get all the arms they want as long as they have money.

Certainly they experience no difficulty in getting ammunition and in living off the country. If they can smuggle a little rice in so much the fatter they, but they can do without it, and even without the supplies they continue to draw from every garrison town we hold in the country, for there are the little patches of yams and potatoes hidden away in the jungles and the mountain rice growing on the hillsides, It would take a long time to dig up the edible roots upon which, at a pinch, the insurgents can live, even if we knew where to find them all. There is a hopeful story in circulation here as well as in Samar, that there comes a period toward the end of the wet season when, owing to the excess of humidity, these roots become unpalatable and even poisonous. This is the time when constant hiking is enjoined, but, up to the present, without success,

HALF OUR MEN SICK OR INVALIDED FOR LIFE

When come up with, the insurgents appear fat and full of fighting as they understand it. Against this fugitive foe is pitted an army of about eight thousand men that is "hacked" by overwork and decimated by disease. There seems to be no healthier place in the world than this Batangas country, when you ride through it as I did, choosing my own time and gait and weather; but forced hiking is a very different thing. What successes have been achieved have entailed fearful loss. The surrender of Cailles last July was compelled by the desperate hiking of our men. It is now well on in November, and more than fifty per cent of these men are on sick report and a large proportion of them appear to be invalided for life. Leaving out the invalids and the wounded, this little army, now barely holding its own in Batangas, is being constantly depleted by the discharge of time-expired men. All the companies (though the war is still very active) have been reduced to the peace strength of one hundred and four men, and indeed very many companies cannot turn out more than forty or fifty men. To cite but one striking, yet by no means exceptional, incident as an illustration, three hundred and eight men are to be discharged from the Second Infantry during the single month of January, 1902, and no arrangements are apparent as yet to fill these actual and prospective vacancies. Much more might be said upon this head, but I will content myself with the statement that, taking no count of the sick and the wounded, and without withdrawing a single organization of those that are in the field, by next March our little army in Malvar's country will be reduced by forty per cent, or say by over three thousand men, This is a serious situation to contemplate. There are certainly no men in the islands that can be put into the gap without weakening too much the forces holding other provinces that appear to be pacified, temporarily at least.

When come up with, the insurgents appear fat and full of fighting as they understand it. Against this fugitive foe is pitted an army of about eight thousand men that is "hacked" by overwork and decimated by disease.

Once in Santo Tomas we rather expected to enter upon closer relations with Lieutenant-General Malvar, We visited the house in which he was born and not'a few of the houses which he owns, and we called upon his brother-in-law, a quiet, gentle little soul, who is being gradually badgered to death by the fact that he is the only possible means of communication between the American authorities and his evasive relative. In default of the great man himself I secured some Malvar literature and broadsheets which are widely circulated throughout the country, I have reproduced one in extenso because it contains the only clear statement of the present insurgent aims and ideals that I have met with.

MALVAR'S NAPOLEONIC BULLETIN

“Attention, Patriots!” runs the order,"Treat considerately and with honor all who are true to the great cause. Exercise severity with criminals and relentlessly pursue those who persist in treason, Above all else, however, good treatment for prisoners of war, observing strictly the laws of civilized warfare and demanding the same treatment in return, Do nothing and, above all else, make no concession that will impair the prestige or injure the future of the people of this archipelago.

Once for all, we must state clearly that the purpose of our contention is liberty without any reservations and an independence which must be perfect and untrammelled. I am in constant communication with the central committees abroad, who have given me ample powers to act. I hope to always deserve and obtain their approval and support.

MIGUEL MALVAR, Lieutenant General,

“Heights of Miquiling, July 31, 1901,”'

Some light is shed upon the manner in which the insurgents secure the sinews of war by the following paragraph which I extract from a general order of Malvar that I came across in Tanauan:

The department commanders will transmit to these headquarters tri-monthly, if possible, all the details of the collection of rents and taxes which have taken place in their departments, In this way subordinate officers will not have to make returns, and so all danger of misapplication of the funds which are raised by the people of the towns and the country for the sacred purpose of national defence will be removed.

A FILIPINO “FLYING DUTCHMAN”

Faint and shadowy indeed remains the figure of Miguel Malvar even when, in pursuit of a better portrait, you have travelled as we are travelling now in the refreshing shadow of the Heights of Miquiling in whose fastnesses he camps. He does not belong to the gente fina; he is a plain countryman with but little education; he has neither studied long and brilliantly at home, like the cutthroat Lukban, nor yet in the universities of Europe, like the martyr Rizal, He comes of good plain people who have lived for generations in the Batangas country, acquiring considerable wealth and a reputation for honesty and square dealing. However, I am not in the least at a loss to give you a description of Don Miguel. I have at least twenty in my possession, all vouched for by the necessary affidavits and witnessed not a few before the parish priests.

He comes of good plain people who have lived for generations in the Batangas country, acquiring considerable wealth and a reputation for honesty and square dealing.

The trouble is that all these descriptions differ radically, and no man can pass along the Batangas highway without fitting in to one or another of them, He rarely camps with his troops, generally with but a friend or two, his Xanthippean wife, a boy to boil his rice, a carabao and a bull-cart. This is the Ma lvar outfit. Within a mile or so of where he camps, in a circle about the place, are detached columns of twenty or thirty men each. His camp is pitched on the brink of some deep barranca, one of those fissures of the earth that run through the Batangas country. The moment a gun is fired Don Miguel disappears and our fellows begin the unsatisfactory search for a needle in a haystack, The only hope the soldiers entertain of ever laying hands on Don Miguel 1s through the striking personality of his wife, Doña Placida. All descriptions agree here. Doña Placida is a squat, cross-eyed woman with a masterful voice and a temper. As a result, all the cross-eyed women in Batangas spend much time in prison, but hitherto Doña Placida has escaped.

WHY WE CAN'T CATCH MALVAR

There are many stories told of Don Miguel's visits to town, and they are not the legends which grow up around every successful guerilla chief: there is much documentary evidence to support them. He visits an army post dressed just like any other country tao, with his shirt outside his homespun trousers, riding a carabao with his favorite gamecock under his arm. He comes to town in amigo clothes to attend to his own affairs, to hear mass, or to barter with our soldiers for plug tobacco, or to remind the patriots within our lines to pay their assessments to the insurgent treasury. In this guise he has entered Calamba on market-day; Lipa, too, when all were celebrating our Lady of the Rosary. He has passed in and out among thousands of people, each and every one of whom knew and worshipped him, The secret known to hundreds was kept, and among the thousands who could have betrayed him not one was tempted to do so by the reward we offer, though that is large, far beyond the Filipino dream of avarice. I do not wish to exaggerate, but I think it well to appreciate the calibre of our antagonists.

The muddy road grows into a broad and stately avenue. Collections of nipa huts crop up on every side, Soon the broad waters of Lake Bay spread out before us, and there, fretting and fuming for the fray, lies the armored tugboat Napidan with Captain O'Connell on the bridge. An army friend comes galloping out to meet us from Calamba and shouts breathlessly, while yet a great way off: “Have you been attacked?” and his face falls when we answer “No,” as it afterward appears our good fortune has cost him a dinner of twelve covers at the Café Luzon.

“No, we didn't see Malvar, not even his tail-feathers,” said the sad trooper, “'and I ain't ever a-going to,” “But he has seen us,” answered the cheerful trooper. “You can bet he hasn't taken his eyes off us since we left Lipa,”

But that is another story. It may be running in the Tagalog bush papers, but I cannot lay it before my readers.