The Last General Issue

Major Simeon Ola: Correcting the misconceptions and falsehood

That Simeon Ola led men in a campaign against the Americans in Bicol until 1903 is an undeniable fact. That he was the last general to surrender is not. Claims that he was a general are spurious, and he had already surrendered earlier in 1901. It would do well to separate fact from fiction, and cease the promotion of myth and untruths. It is time to correct misconceptions and falsehoods; otherwise, in the words of historian John Arcilla, S.J., "we would be glorifying fiction".

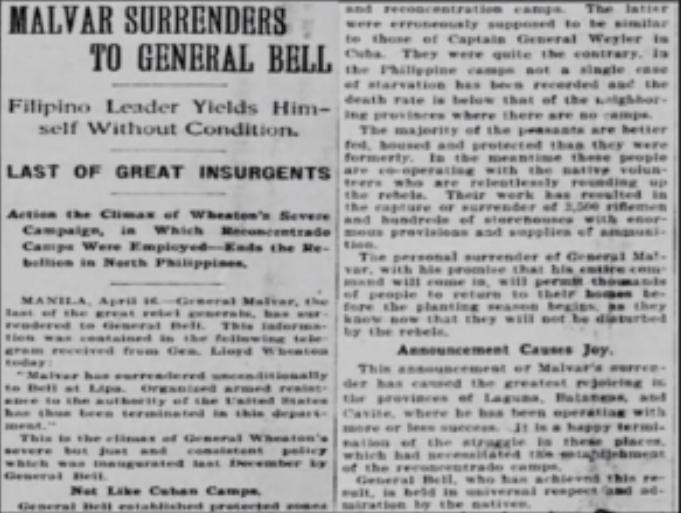

It was General Miguel Malvar's surrender in April, 1902 that prompted the Americans to declare the end of the Philippine American war on July 4, 1902. In newspapers reports of his capitulation, he was described as "The last great insurgent", to characterize his stature and the significance of his resistance. He was the de facto president of the Philippine Republic, the highest ranking officer and supreme commander of the entire Republican forces at the time of his surrender, and, in the words of O.D. Corpuz, "the prized catch" along with Lukban, who was caught earlier in February 1902. He was no ordinary general. He was at the helm of the army and the successor of Aguinaldo, and to U.S. leadership, he was the symbol of Filipino resistance. The description the last general to surrender to describe Malvar alludes to not just his rank but primarily, his importance and consequence, and how those weighed in on the American's decision to formally end the war. (See Malvar's surrender signals the end of the Philippine American War).

Filipino resistance did not end with the declaration of peace. Pockets of resistance continued, for several years with the Philippine Constabulary now taking the lead to quell the disturbances. One figure who was causing trouble was Simeon Ola, who roamed the mountains of Bicol until he and his men were finally subdued in 1903. In the last fifty years or so, Ola had been attributed to as the "last general to surrender". Ola had mentioned in his memoirs that he had been promoted to General.

Historian Norman G. Owen takes issue with Simeon Ola being the last general to surrender and refers to his article "Winding Down the War in Albay, 1900-1903." He states:

"There are at least two potential problems with regarding Ola as the last general to surrender. First, he had actually surrendered before (as one of the officers of Vito Belarmino), in 1901, before returning to the hills. Second, there is no documentation of his commissioning as a general by any recognized authority of the Philippine Republic."

Before diving into the particular points that Norman Owen raises, it would be best to first describe who he is and the sum and substance of his work. Norman Owen is the author of The Bikol Blend: Bikolanos and Their History , a landmark collection of 11 essays encompassing more than 20 years of research on Bicol history, ranging from "broad synthetic surveys of the social and economic history of the region, and its century-long dependence on abaca, to detailed treatments of the careers of an eighteenth-century Spanish missionary and a nineteenth-century American abaca-trading firm". One of the essays, Winding Down the War in Albay, 1900- 1903, "traces the course of accommodation between Bikolano elite and the emergent American colonial order."

Bruce Cruikshank (Hastings College) in his review (create link of underlined to file/image 003) of Owen's book states:

"One of the most productive scholars in the work to date is Norman Owen. He has provided the sort of archival digging that is a model for all of us, along with the comparative and theoretical sophistication that quality historical work demands.

This book of essays is also evidence of how much remains to be done as we try to archive this standard of quality and a fuller understanding of the multiple dimensions and motives of the variety of historical actors in the rural and provincial Philippines.

John A. Larkin (The Place of Local History in Philippine Historiography, Journal of Southeast Asian History, September 1967) argued that Philippine history had heretofore had concentrated too much on events and governing elites centered on Manila and in the imperial capitals of Madrid or Washington, D.C. The task as now to move away from the metropolis to rediscover the rest of the story, to look at local elites and the common folks in provinces, cities and towns. When we had done this, he forecast, we would have the regional and provincial studies to use as "building blocks" to construct a fuller picture of the Philippine past, indeed to construct a history of the archipelago."

-

With that, we now proceed to Owen's points:

-

Ola had already surrendered earlier in July 1901 with Belarmino prior to his final capitulation in 1903.

It is widely accepted that Ola served as a major under General Vito Belarmino, the politico military commander of Bicol. For his surrender with Belarmino in 1901, Owen cites the following sources: a) the US War Department records (1902); b) various letters written to Elias Ataviado when he was compiling his study on the revolution in Albay; and c) a letter by Col. Harry Hill Bandholtz in his papers at the University of Michigan.

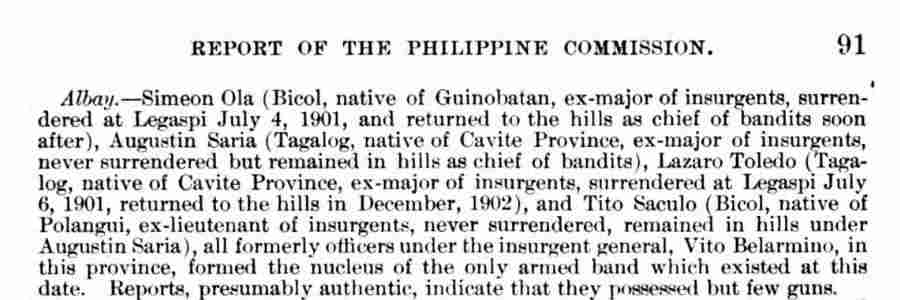

The US War Department reports which rate high in validity and reliability as a primary source, are provided below. Official reports of the War Department confirm that Ola did indeed surrender with Belarmino in July, 1901 with the rank of major.

-

From the Annual Report of the Second District Philippines Constabulary, June 1903

Ola Surrenders at Legaspi on July 4, 1901 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE SECOND DISTRICT PHILIPPINES CONSTABULARY FOR THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 1903, COL. H. H. BANDHOLTZ, U.S. ARMY, COMMANDING.HEADQUARTERS SECOND DISTRICT PHILIPPINES CONSTABULARY,

Lucena, Tayabas July 1903

The ADJUTANT, PHILIPPINES CONSTABULARY, Manila

Sir: In compliance with telegraphic instructions from Headquarters Philippines Constabulary dated Manila May 1903 have the honor submit the following report covering Operations occurrences and conditions the various provinces constituting the second constabulary district the fiscal year ending June 1903:

(contd.)

Albay—Simeon Ola (Bicol, native of Guinobatan, ex-major of insurgents, surrendered at Legaspi July 4, 1901, and returned to the hills as chief of bandits soon after), Augustin Saria (Tagalog, native of Cavite Province, ex-major of insurgents, never surrendered but remained in hills as chief of bandits), Lazaro Toledo log, native of Cavite Province, ex-major of insurgents, surrendered at Legaspi July 6, 1901, returned to the hills in December, 1902), and Tito Saculo (Bicol, native of Polangui, ex-lieutenant of insurgents, never surrendered, remained in hills under Augustin Saria), all formerly officers under the insurgent general, Vito Belarmino, in this province, formed the nucleus of the only armed band which existed at this date. Reports, presumably authentic, indicate that they possessed but few guns.

-

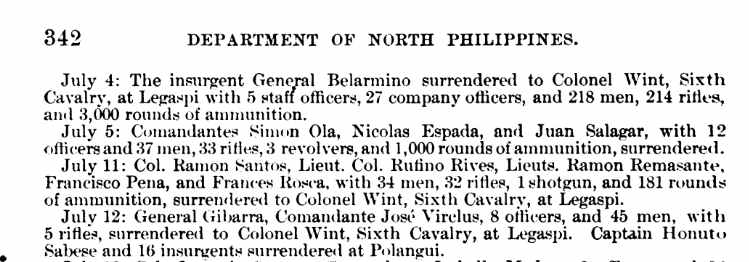

From the Reports of Operations in the Fourth Separate Brigade, August 1902

Ola Surrenders with General Belarmino on July 5, 1901 HEADQUARTERS FOURTH SEPARATE BRIGADE

Nueva Caceres, Ambon Camarines, P. I., August 2, 1902

THE ADJUTANT-GENERAL, DEPARTMENT NORTH PHILIPINES, Manila P.I.

Sir: The last report from these headquarters was made May 21, 1901, at which time this command was denominated the third district, Department of Southern Luzon, and comprised the provinces of Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Albay, and Burias, divided into sub- districts, as follows:

(contd.)

July 4: The insurgent General Belarmino surrendered to Colonel Wint, Sixth Cavalry, at Legaspi with 5 staff officers, 27 company officers, and 218 men, 214 rifles, and 3,000 rounds of ammunition.

July 5: Comandantes Simon Ola, Nicolas Espada, and Juan Salagar, with 12 officers and 37 men, 33 rifles, 3 revolvers, and 1,000 rounds of ammunition, surrendered.

July 11: Col. Ramon Santos, Lieut. Col. Rufino Rives, Lieuts. Ramon Remasante,

Francisco Pena, and Frances Rosea, with 34 men, 32 rifles, 1 shotgun, and 181 rounds of ammunition, surrendered to Colonel Wint, Sixth Cavalry, at Legaspi.

-

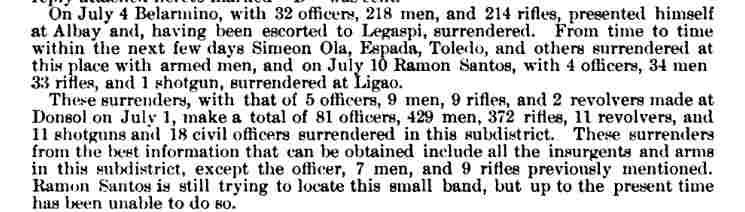

From the Annual reports of the War Department. 1902 v.9.

Belarmino surrenders with 32 Officers on July 4, 1901 Headquarters Subdistrict of Albay,

Legaspi, Albay, P. I., August I3, 1901

The Adjutant-General Department of Southern Luzon,, Manila, P.I.

(Through headquarters third district, Department of Southern Luzon, Nueva Caceres, P. I.)Sir: I have the honor to submit the following report of operations against the insurgent forces in the subdistrict, which ended in the surrender of the insurgent, General Belarmino, and all of his forces and arms except a small force composed of Lieut. Augustin Sariaya and 7 men, which has in its possession 9 rifles. This force belonged to Comandante Toledo's band and refused to surrender, and when last heard of was supposed to be attempting to escape to the north, with a view to joining some force still in the field:

(contd.)

On July 4 Belarmino, with 32 officers, 218 men, and 214 rifles, presented himself at Albay and, having been escorted to Legaspi, surrendered. From time to time within the next few days Simeon Ola, Espada, Toledo, and others surrendered at this place with armed men, and on July 10 Ramon Santos, with 4 officers, 34 men 33 rifles, and 1 shotgun, surrendered at Ligao.

Why did Ola return to the hills?

If Ola had already surrendered in July 1901, what prompted him to pick up his rifle again and return to the life of an insurgent? Dean Conant Worcester , member of the Philippine Commission from 1900 to 1913, provided an interesting insight in his work The Philippines: Past and Present. He suggests that Ola squabbled with the Jaucians, also residents of Guinobatan with whom he was at odds, and that it was this feud that triggered his return to the hills.

"In 1902 an outlaw Tayabas Province who made his living by organizing political conspiracies and collecting contributions in the name patriotism, who was known as José Roldan when operating adjoining provinces but had an alias in Tayabas, found his life made so uncomfortable by the constabulary of that province that he transferred his operations to Albay. There he affiliated himself with a few ex-Insurgent officers who had turned outlaws instead of surrendering, and with oath violators, and began the same kind of political operations which he had carried out in Tayabas, the principal feature of his work being the collection of “contributions."

The troubles in Albay were encouraged by wealthy Filipinos who saw in them a probable opportunity to acquire valuable hemp lands at bottom prices, for people dependent on their hemp fields, if prevented from working them, might in the end be forced to sell them. Roldan soon lost standing with his new organization because it was found that he was using for his personal benefit the money which he collected.

About this time one Simeon Ola joined his organization. Ola was a native of Albay, where he had been an Insurgent major under the command of the Tagálog general, Belarmino. His temporary rank had gone to his head, and he is reported to have shown considerable severity and hauteur in his treatment of his former neighbours in Guinobatan, to which place he had returned at the close of the insurrection. Meanwhile, a wealthy Chinese mestizo named Don Circilio Jaucian, on whom Ola, during his brief career as an Insurgent officer, had laid a heavy hand, had become presidente of the town.

Smarting under the indignities which he had suffered, Jaucian made it very uncomfortable for the former major, and in ways well understood in Malay countries brought it home to the latter that their positions had been reversed. Ola's house was the mysteriously burned and his life in Guinobatan was made so unbearable that he took to the hills.

Ola had held higher military rank than had any of his outlaw associates, and he became their dominating spirit. He had no grievance against the Americans, but took every opportunity to avenge himself on the caciques of Guinobatan, his native town."

In Jungle Patrol, the Story of the Philippine Constabulary (1901-1936), Vic Hurley also corroborates Worcester's accounts:

"Ola had been an insurgent Major under General Belarmine (sic), the Tagalog leader. Ola was a small man and his rank had given him delusions of grandeur. He had taken advantage of his Majority to treat his neighbors with great severity, with the result that he had become a pariah in his native village of Guinobatan.

Among the natives who had suffered at the hands of Ola was one Cirilio Juacian, a Chinese half-caste who had now risen to affluence to become Presidente of Guinobatan. He had immediately driven Ola into the hills, where the ex-Major affiliated first with Jose Roldan and later with the formidable Toledo."

Colonel Bandholtz also provides a similar perspective. The following account of the Albay insurrection is taken wholly from his report dated December 15:

"The outbreak in Albay differed in many respects from that of any other province Some the ladron leaders like Saria and Saculo had always been ladrones and followed the bandit life for the love of it. Ola and some others were unquestionably driven to the hills by the persecutions of their local enemies and municipal officials, and their followers augmented rapidly and they were successful from the beginning that their heads were naturally turned."

(Stetka Gyula: Harry Hill Bandholtz (1864–1925) tábornok portréja (olajfestmény, 1920)) Bandholtz, Hurley and Worcester cite Ola's feud with Jaucian and the locals of Guinobatan as a significant factor in his return to the hills. Revenge on his enemies more than patriotism could well have been the dominant motivation to drive him back to the "insurgent" life.

-

From the Annual Report of the Second District Philippines Constabulary, June 1903

-

There is no documentation of Ola's commissioning as a general by any recognized authority of the Philippine Republic.

At the time of Belarmino's surrender in July 1901, Aguinaldo had already been captured, and Malvar had assumed the position of supreme commander of what remained of the Republican forces. By then, the only person that could promote Ola to the rank of general was Malvar himself, by virtue of his higher position in the military hierarchy. Norman Owen expresses his doubts over this "appointment".

"For his claim to the rank of general, however, there is no evidence but Ola's own testimony that he was told to continue fighting by Belarmino and that later he was commissioned by General Malvar, who succeeded Aguinaldo as commander-in-chief. Now it is entirely understandable that any actual papers from the time relevant to this might well have been lost in the chaos of the time, so their absence is not in itself significant, BUT it leaves Ola's own claim unsupported. And since he did surrender with Belarmino, we may wonder about the assertion that Vito Belarmino told him to go on fighting."

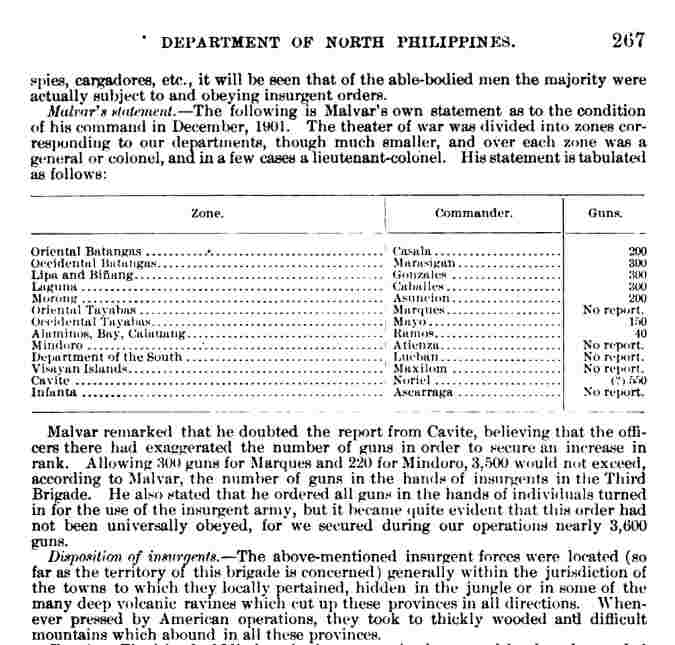

Condition of Malvar's Command in December, 1901

Not only is Ola's claim unsupported by any other evidence, but they go against the pronouncements of Malvar, the very person who Ola identifies as the superior who promoted him.

"It is standard research procedure to evaluate necessarily limited and obviously prejudicial personal memoirs against the total historical context when they were written and which they only partially describe."

- Jose Arcilla, S.J.

Malvar's own statement as to the condition of his command in December, 1901 did not include Ola, a clear and direct invalidation of Ola's assertions. Commanders in zones were either generals, colonels, or lieutenant colonels. Samar was further south than Bicol, yet Gen. Lukban, the politico-military head of the area, was mentioned in the report. Even if it were a simple oversight, one has to wonder about Ola's stature for him to be overlooked, given the diminished size of the army, as the forces of Tinio, Cailles, Moxica, Belarmino, et al had already surrendered or had been captured. Malvar's statement was part of Bells' report released in September 1902, long after his surrender. Malvar had been debriefed and interrogated several times, and this account had several opportunities to be amended to include additional testimonies initially missed. To reiterate, Malvar who supposedly commissioned Ola as general, omitted him (Ola) when describing the officers under his command. Ola's claim that he was a general has been rebuked and therefore cannot be accepted.

When referring to Ola in his official report, Bandholtz qualifies the use of the title, and places quotation marks on the abbreviation of the term general ("Gen."), indicating skepticism on his rank. This illustrates the credibility issues related to his rank even back then, especially when the other U.S. War Department reports referred to him as an ex-major.

Why would Ola claim that he was a general?

Accounts of Ola's capitulation shed light on his nature. How he behaved after his surrender is revealing. Charles Burke Elliott in The Philippines to the End of the Commission Government: A Study in Tropical Democracy narrates that Ola was the reason for the execution of many of his men:

"During the winter months of 1903-1904 the constabulary carried active campaign Albay against one Simeon Ola and a large body ladrones. Ola finally surrendered to Colonel H. Bandholtz, under circumstances which induced his friends in the United States to claim that he had been offered immunity from punishment. There never was better illustration of the habit of certain good people of springing to the defense of any scoundrel upon whom the law has succeeded in getting in its clutches, particularly when by so doing they can strike at the reputation of some officer. Ola turned state's evidence and cheerfully aided sending many of his associates to the scaffold but never made any claim that had been promised immunity."

Vic Hurley's accounts (Jungle Patrol, the Story of the Philippine Constabulary (1901-1936) ) are more candid in explaining how Ola literally got away without being severely punished:

Ola didn't hang -- he was too smart to pay any penalty for a lifetime of brigandage. Ola had brought in about 600 men, as the milder spirits had been turned loose immediately. Several hundred of these were in turn released. A few were tried under the vagrancy law and given road-work sentences of six months to two years. About sixty were sentenced to Bilibid for sedition, and twelve were hanged.

When Ola turned state's witness, he was given a 30-year suspended sentence."

It is Ola himself who has put his character into question. Ola's actions are his own. Turning state witness and testifying against his men in exchange for his liberty reveals the lengths he has gone, and proves that there were unconscionable lines he would cross for his personal gain. In completing a real profile of the man, one has to take into account his shady involvement with the outlaw Josè Roldan, his audacious display of power as an officer, the harshness of his treatment of the townspeople of Guinobatan which led to personal conflicts, and the dishonorable betrayal of his troops to his American captors. Given Ola's track record, his proclivity to punish the caciques of Guinobatan at every opportunity, and his "delusions of grandeur" as Hurley had described, it is not surprising why he would make false claims about his rank to enhance his standing.

"The primary task, therefore, is to look for sources of history and verify them. Only after finishing this preliminary search and evaluation can one put these disparate sources of information together and create an intelligible pattern which we call history.

Save for a few exceptions, much of what has been accepted today as "history" is no better than propaganda and pseudo-scholarship. The point is not to say whether there are Filipino heroes or not; rather an attempt should be made to show what makes them heroic."

- Jose Arcilla, S.J.

The established "intelligible pattern" points to an unscrupulous and peculiar character. Particular details about Ola's persona cannot be overlooked, and must be carefully considered when making a complete evaluation of his nature and disposition. The ultimate aim is not to cast doubt or to discredit, but to facilitate a better understanding of the constitution of historical figures if we are to learn from their example. Maturity and critical thinking are necessary to establish and accept who historical figures really are, and to avoid hero-worshipping and turning a blind-eye to their fundamental flaws and weaknesses for fear of compromising their "stature" and knocking them off their unwarranted pedestals.

Patriots and Brigands: Separating the chaff from the grain.

The Brigandage Act of 1902 deemed all still fighting the Americans post as brigands and bandits, thus, misclassifying and trivializing legitimate freedom fighters like Luciano San Miguel as tulisanes instead of the true patriots that they were. On the same token, lazy historians, taking issue with the biased categorization and using it as a convenient pretext, were also quick to exonerate everyone misclassified as non-brigands, without regard to context, nuances, and circumstances.

Thieves, murderers, bandits did exist with freedom fighters. The chaff needs to be separated from the grain, tedious as the required effort may be. Each individual of consequence must be subjected to a thorough examination. Each case should be considered on its own merits, or lack thereof. The biggest disservice is clustering the commendable with the unworthy. With the incorrect blanket exoneration of every one, the real patriots were not properly distinguished as the real outlaws were cleared as well. The Luciano San Miguels deserve better.

We therefore ask the relevant questions of Ola. To what extent does his involvement in banditry and illegal activities come into play? How much did local politics, revenge, and personal conflicts influence his life outside the fold? By how much did his association with Roldan taint his persona and determine his activities? How much of his ladron tendencies can be ruled out?Was he really still fighting for a concept of country and freedom when he returned to the hills? What was his primary purpose? The answers to these difficult questions are available and need to be discussed further if we are to establish who the man really was.

The Americans "labelling" Ola as a ladron is secondary. Ola's character and actions are more telling whether he was indeed a ladron or not

Correcting the falsehood

That Simeon Ola led men in a campaign against the Americans in Bicol until 1903 is an undeniable fact. That he was the last general to surrender is not. Claims that he was a general are spurious, and he had already surrendered earlier in 1901. It would do well to separate fact from fiction, and cease the promotion of myth and untruths. It is time to correct misconceptions and falsehoods; otherwise, in the words of historian John Arcilla, S.J., "we would be glorifying fiction".

If history seeks the truth, then intellectual dishonesty cannot be tolerated. Lies should not be propagated.