The 2nd President

Malvar is not mentioned in the roster of Philippine presidents despite overwhelming evidence indicating he was a direct successor to Aguinaldo’s presidency. This glaring omission needs to be corrected through the leadership and initiative of the National Historic Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) so that he can take his rightful place in the prestigious roll and be officially recognized as a President of the Philippines under the First Republic.

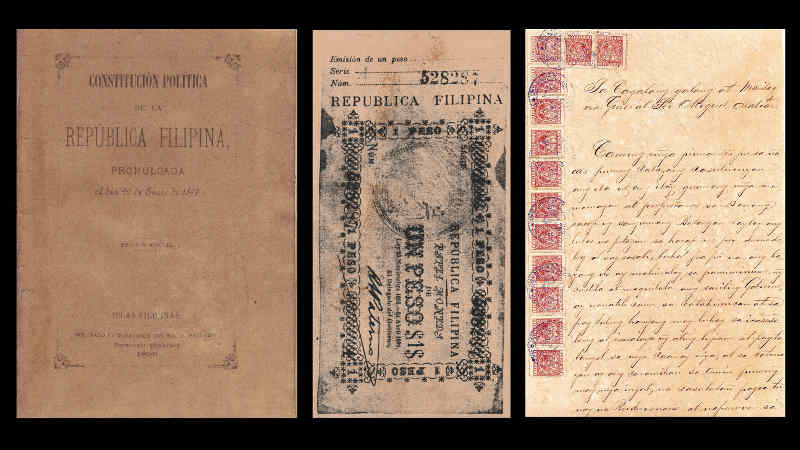

The First Philippine Republic was formally established with the proclamation of the Malolos Constitution on January 21, 1899, in Malolos, Bulacan. The First Philippine Republic is a legitimate government, with functioning institutions.

"With the compromises effected, the government leaders and the Congress prepared for the ceremonies scheduled for 23 January. Aguinaldo's message promulgating the Constitution was dated 21 January. The promulgation was the first order of business on the 23rd. After this the members of the Assembly took the oath to the Constitution. The proclamation of the Republic followed. Next came the proclamation of Aguinaldo as President; he was formally notified and invited to appear before the Assembly, at which he took his oath of office and delivered a speech."

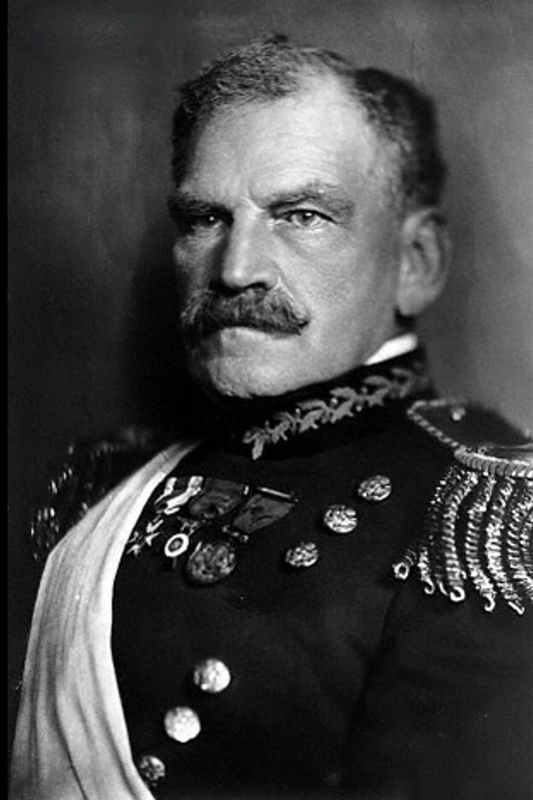

Emilio Aguinaldo became the inaugural president of the First Philippine Republic. He held that office until March 1901, when he was captured by United States forces during the Philippine–American War (1899–1902). Miguel Malvar assumed full command over the entire forces in July 1901, with the imprimatur of the Hong Kong Junta (Central Committee in Hong Kong). For over a year until his surrender on April 16, 1902, Malvar was the de facto president of the Philippines.

Historian Luis C. Dery in his book "Army of the Philippine Republic" explains the basis of Malvar's assumption of power:

"The June 27, 1900 decree specifically designated General Trias to succeed Aguinaldo in the event of his capture, death, or whatever form of incapacity to perform the function of office of the President and Commander-in-chief of the Philippine Republic and its Army. General Miguel Malvar became a contender to Aguinaldo's post because of the fact that at the time General Trias surrendered, Malvar was Trias' second-in-command. Thus, by virtue of Aguinaldo's succession' decrees of February 16, 1899; November 13, 1899; and June 27, 1900, General Malvar, with Trias' surrender, became the logical successor to Aguinaldo's post and to the leadership of the Filipino struggle against the Americans."

"The Filipino Revolutionary committee (or Hong Kong Junta) officially confirmed Malvar's assumption of Aguinaldo's post. This was in consonance with a provision of Aguinaldo’s June 27, 1900 decree, where it vested the Hong Kong Junta with the authority to assume Aguinaldo's post during the interregnum following his death or captivity while looking for a successor. It was this authority that the Hong Kong Junta invoked when it confirmed Malvar as Aguinaldo's successor."

Key points from above are: 1) Aguinaldo's death or captivity triggers the succession decrees; and, 2) the succession is to "Aguinaldo's post" to perform the function of office of the President and Commander-in-chief of the Philippine Republic and its Army. The leadership position of the Filipino struggle against the Americans is for both the Presidency and the Supreme Command of the Forces, not merely one or the other.

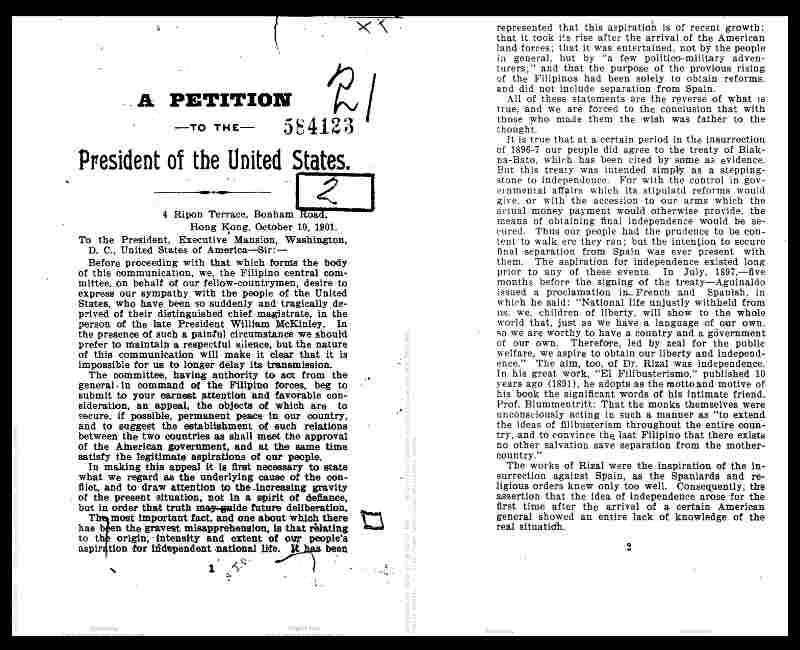

The Central Committee in Hong Kong, in a letter directed to the U.S. President in October 1901 appealing for independence, also clearly defined the status and position of Malvar, and the relationship between Malvar and the committee:

"The committee, having authority to act from the general in command of the Filipino forces, beg to submit for your earnest attention and favorable consideration, an appeal, the objects of which are to secure, if possible, permanent peace in our country, and to suggest the establishment of such relations between the two countries as shall meet the approval of the American government, and at the same time satisfy the legitimate aspirations of our people. (contd)

In a recent proclamation, Gen. Malvar, now in command of our forces, declares: "Our banner is not that of war against America, but of rightful defense of a people whose most cherished and sacred rights have been trampled underfoot." He further declares that the aim is not to "kill all Americans, who, lie ourselves, have mothers, wives, daughters or sons who would mourn their loss," but to defend "our legitimate right to have a government of our own and an independent life." In this he expresses with dignity and precision the sentiments of every right-thinking Filipino.

Without necessarily seeking for recognition of our authority, we consider it proper to state, very briefly, by what authority we act:

In an official communication, dated 31st of July, 1901, Gen. Miguel Malvar, in supreme command of the Filipino forces, confirms the power previously held by this committee, and supplements it, declaring us to be the body legally representing those in arms, and recognizing in us the fullest powers."

On July 13, 1901, in a proclamation addressed to the Filipino people and its army, Miguel Malvar announced that he was taking overall command, albeit reluctantly, at the behest of the Central Committee, because of the necessity of having a leader to direct the struggle:

"Events known to all and of sad misfortune to the country, have placed me by reason of my rank, in the Supreme Command of our Liberating Forces.

I was desirous that, as when I assumed the Superior Commander ship of Southern Luzon, a General Assembly of those struggling and working for the common cause, should meet and designate who was to assume it. But this Assembly is impossible for the present, and being pressed on the other hand repeatedly by our Committees of Independence abroad as also by prominent persons in the Archipelago, and it becoming daily more urgent and necessary that there should be a Superior Commander to give greater stability and strength to our defense, in order to save it from the grave danger menacing it, I assume this command from this date until said Assembly can meet, when I will gladly withdraw in favor of the person who may be elected by it, my only ambition and my highest desire being to see our land free from the foreign yoke.

(contd)

This is my plan:

Consideration, honors and kindness for good and true patriots; severity against the malicious and criminals; hard inflexibility towards those who persist in being traitors; humanity towards the enemy, the laws of warfare being strictly observed, but their strict observance also being required, and no yielding with regard to the future of the Archipelago. I shall admit nothing which has no independence as its basis. For which negotiations as also for any other acts, I have granted and do hereby grant the fullest powers to the Central Filipino Committee abroad, whose decisions and recommendations I always intend to observe in all my actions."

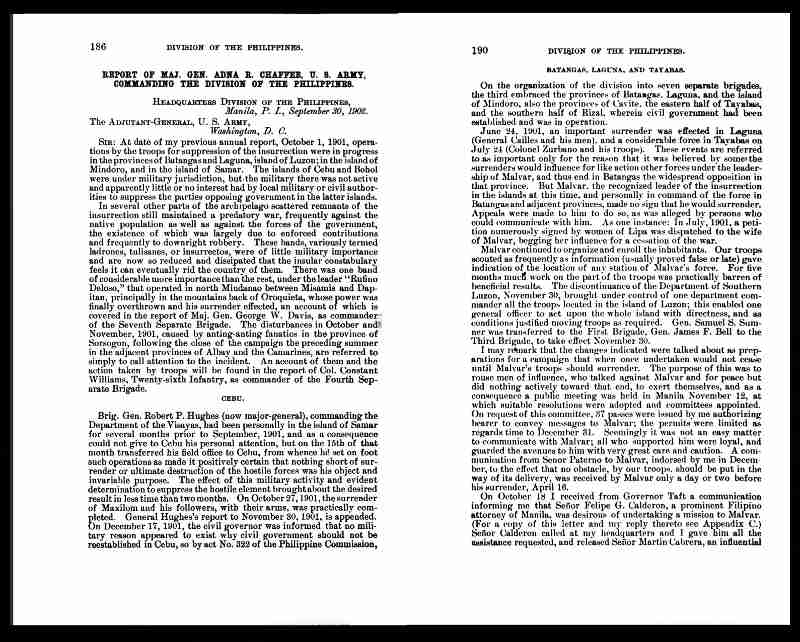

Malvar's standing and position was also acknowledged and validated by Maj. Gen. Adna R. Chafee, the Military Governor of the Philippines, from July 1901 to October 1902. In a report addressed to the Adjutant-General, U. S. Army, Washington, D. C., dated September 30, 1903, he states:

"June 24, 1901, an important surrender was effected in Laguna (General Cailles and his men), and a considerable force in Tayabas on July 24 (Colonel Zurbano and his troops). These events are referred to as important only for the reason that it was believed by some the surrenders would influence for like action other forces under the leadership of Malvar, and thus end in Batangas the widespread opposition in that province. But Malvar, the recognized leader of the insurrection in the islands at this time, and personally in command of the force in Batangas and adjacent provinces, made no sign that he would surrender. Appeals were made to him to do so, as was alleged by persons who could communicate with him. As one instance: In July, 1901, a petition numerously signed by women of Lipa was dispatched to the wife of Malvar, begging her influence for a cessation of the war."

Press reports carried by numerous newspapers at different points in time also show the relationship between Malvar and the Central Filipino Committee/Hong Kong junta. The succeeding examples below illustrate the symbiotic relationship of the two parties, mutually reinforcing and co-dependent on each other, with Malvar being the more dominant:

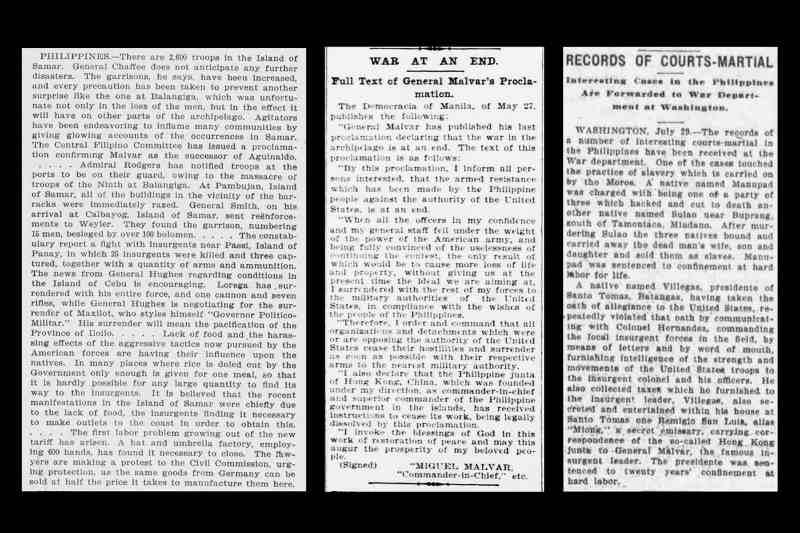

Rural New Yorker, 1901

PHILIPPINES. - There are 2,600 troops in the Island of Samar. General Chaffee does not anticipate any further disasters. The garrisons, he says, have been increased, and every precaution has been taken to prevent another surprise like the one at Balangiga, which was unfortunate not only in the loss of the men, but in the effect (sic) it will have on other parts of the archipelago. Agitators have been endeavoring to inflame many communities by giving glowing accounts of the occurrences in Samar. The Central Filipino Committee has issued a proclamation confirming Malvar as the successor of Aguinaldo.

War at an End, Evening Star, July 09, 1902

"General Malvar has published his last proclamation declaring that the war in the archipelago is at an end. The text of this proclamation is as follows: (contd)

I also declare that the Philippine junta of Hong Kong, China, which was founded under my direction as commander-in-chief and superior commander of the Philippine government in the islands, has received instructions to cease its work, being legally dissolved by this proclamation."

Miguel Malvar

Records of Courts-Martial, Omaha Daily Bee, July 30, 1902

He also collected taxes which he furnished to the insurgent leader, Villegas, also secreted and entertained within his house at Santo Tomas one Remigio San Luis, alias "Miong," a secret emissary, carrying correspondence of the so-called Hong Kong junta to General Malvar, the famous insurgent leader.

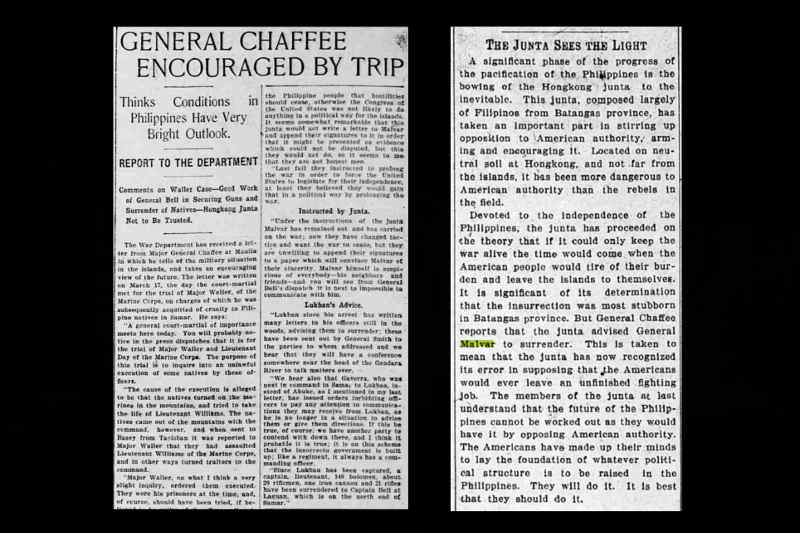

Instructed by the Junta, The Washington Times, April 23, 1902

" Under the instructions of the junta, Malvar has remained out and has carried on the war; now they have changed tactics and want the war to cease, but they are unwilling to append their signatures to a paper which will convince Malvar of their sincerity. Malvar himself is suspicious of everybody -- his neighbors and friends -- and you will see from General Bell's dispatch it is next to impossible to communicate with him."

The Junta Sees the Light, The Minneapolis journal, April 25, 1902

Devoted to the independence of the Philippines, the junta has proceeded on the theory that if it could only keep the war alive the time would come when the American people would tire of their burden and leave the islands to themselves. It is significant of its determination that the insurrection was most stubborn in Batangas province. But General Chaffee reports that the junta advised General Malvar to surrender. This has taken to mean that the junta has now recognized its error in supposing that the Americans would ever leave an unfinished fighting job. The members of the junta at last understand that the future of the Philippines cannot be worked out as they would have it by opposing American authority.

A Glaring Omission

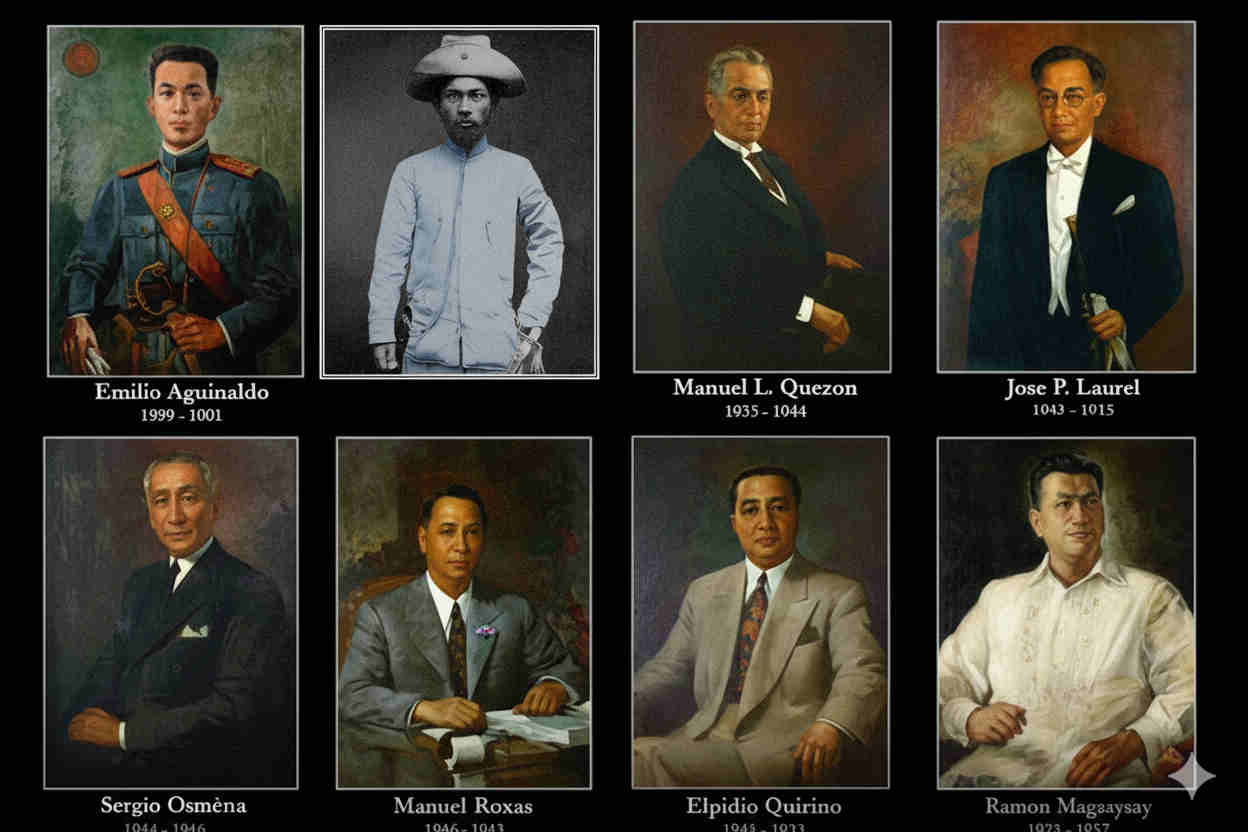

In the official roster of Philippine Presidents of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, Emilio Aguinaldo is the first name on the list as President of the First Philippine Republic and the Malolos Constitution of 1899. Manuel L. Quezon is the second name cited by virtue of being elected to a six-year term in the first national presidential election made possible by the creation of the Commonwealth of the Philippines following the ratification of the 1935 Constitution. There is a 35-year gap between the first and second recognized Presidents of the Philippines.

Malvar is not mentioned in the roster of presidents, despite overwhelming evidence indicating he was a direct successor to Aguinaldo’s presidency.

The legitimacy of Malvar's standing as president is contingent on the legality of the Malolos Republic and its constitution, which determines Aguinaldo's presidency and the succession decrees.

Referring again to the Central Committee's letter directed to the U.S. President, it is clear that Aguinaldo and the Malolos government were not recognized by the Americans then:

"A technical difficulty arises out of the fact that the Philippine government has never received recognition by the United States or by any other sovereign power. It has been contended that there is consequently no Philippine authority with which the American government could negotiate, even if it had the desire, and that to have relations with those claiming such authority would imply a recognition which America cannot and will not give.

We claim to have authority on behalf of the Philippine people--authority which, having been properly conferred, is acknowledged and would be obeyed. But if there is technical validity in the above contention, our people would be prepared to accept an assurance of the ultimate recognition of their rights through an indirect channel, either by proclamation to the Philippine people in general or by an annunciation of policy to the people of America, or by such other method as may be deemed proper. The technical difficulty would thus be surmounted, and the object of this appeal achieved, without giving recognition to say any real or "so-called" Philippine authority. And as soon as peace had been established a constitutional convention could be convened similar to one operating in Cuba, with which all future relations could be held, and by which all differences could be adjusted."

Yet, despite the lack of recognition by the U.S. and other sovereign powers of Aguinaldo's presidency during Philippine-American war because he was considered an insurrecto, and the resistance, an insurrection, this has not prevented the NHCP to acknowledge Aguinaldo as the first Philippine president.

The recognition, thus, by the NHCP of Aguinaldo's position is not contingent on the validation of the First Philippine Republic by the U.S. or the international community at that time. Consequently, the recognition of the institutions of the First Philippine Republic is also duly accepted by the NHCP, including succession decrees.

By including Aguinaldo in the determination of the roster of Philippine presidents, the NHCP has already established its own guidelines and parameters and has elected to disregard the opinion of the U.S. and international community on this matter and render it irrelevant. To exclude Malvar as president would show bias and lack of consistency in the application of the rules and criteria.

NHCP should be reminded of the words of the Philippine Central Committee: We claim to have authority on behalf of the Philippine people--authority which, having been properly conferred, is acknowledged and would be obeyed.

This is the authority that counts the most. Sovereignty emanates from the Philippine people as embodied in the Malolos Constitution. This sovereignty existed before the war between the Filipinos and the Americans broke out, and even before the United States exercised dominion in the Philippines.

There is the view that the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo by American forces on March 23, 1901, in Palanan, Isabela, and his pledge of allegiance soon after, effectively dissolved the First Republic. This position does not hold because the succession decrees are automatically triggered and entrust "the Hong Kong Junta with the authority to assume Aguinaldo's post during the interregnum following his death or captivity while looking for a successor."

The succession decrees assured the continuation of the Republic, demonstrating the foresight of the framers in anticipating the contingency of the capture and incapacity of Aguinaldo, and ensuring that the institution that Aguinaldo represented did not end.

Malvar also demonstrates his initiative and resolve to address the vacuum in leadership in his April 19, 1901 letter to Aguinaldo upon learning of the latter's capture:

"MY RESPECTED CHIEF AND SIR:

(contd)

From the time that Señor Trias changed attitude, I took the liberty to assume the command which he forsook, not because I thought myself worthy of it, nor on account of my past services, which up to the present time have been no better than those of a poor soldier, but by regular order of seniority, and to prevent the complete demoralization of this part of our army.

For the present I shall await the orders of my Chief with respect to the conduct of our politico-military organization, but I should regret to refuse for the first time, and you would have to pardon the first proof of insubordination or lack of discipline, should you by chance order me to surrender my arms."

Historians and scholars can debate and determine when the actual end of the First Republic occurred. It could have been with the surrender of Malvar. Or it could be with the dissolution of the Philippine Central Committee. That finality is beyond the scope of this piece. It is quite clear, however, that the First Philippine Republic did not end with the capture of Aguinaldo in March 1901. It was kept alive by the ascendancy of Malvar.

Another flawed misconception is that the U.S. establishment of civilian control exercising executive power in July 1901, concurrent with military control in selected areas, abolished the First Republic. This is not a valid view. The Malolos Republic was not recognized by the US government at the outset; therefore, successive actions on their part to abolish the very thing they did not acknowledge to begin with is absurd.

To reiterate, the NHCP's justification for the recognition of Aguinaldo is not contingent on U.S. or international positions. Succeeding unilateral executive actions by the U.S. also should not be the basis for determining the dissolution of the Malolos Republic. The First Republic, through the continuation of the "insurgency," was still alive and functioning even if beleaguered and in a state of siege. Subjugation by the American colonizers was not complete yet.

Although interrupted by the Philippine-American War, the demise of the Malolos Republic is not determined by US actions or declarations (i.e., establishment of the Civil government) but by the factors that led to its own inherent termination and finish (i.e., end of the Philippine Committee; effective collapse of entire Philippine Army). To go against that principle would be prejudicial against Malvar.

Rectifying Mistakes

There is a precedent for correcting mistakes and addressing oversight. José P. Laurel's Second Philippine Republic presidency of the Japanese-sponsored government during World War II was not recognized initially because it overlapped with Quezon's exiled Commonwealth term. It was only in the 1960s that Laurel's presidency was legally recognized.

Whether the official declaration is executed through an act of Congress or through an executive order, the NHCP needs to make the initial determination. Their opinion and position on the matter, whether for or against it, must be articulated. Inaction by the NHCP denies a deserving man his rightful place in history, or at the very least, deprives the man's legacy of the respect it deserves and should be accorded if the reasons why his case is precluded are not presented.

A comment on the validity of Bonifacio as president

Some historians also call for the recognition of Andres Bonifacio as president. To differentiate, Malvar's case rests on the recognition of succession within a valid government (First Republic). Bonifacio's situation requires the substantiation that the Katipunan was more than just a secret society but an accepted government.

The cases of Malvar and Bonifacio are separate, mutually exclusive issues and are not dependent on each other. The trinity of Rizal, Aguinaldo and Bonifacio occupy the highest places in the annals of Philippine history. Malvar does not fall under the same category as these men. Nevertheless, the evaluation and prioritization of their circumstances should depend on the merits of their cases rather than on their stature.