Reconcentration and Bell’s Campaign

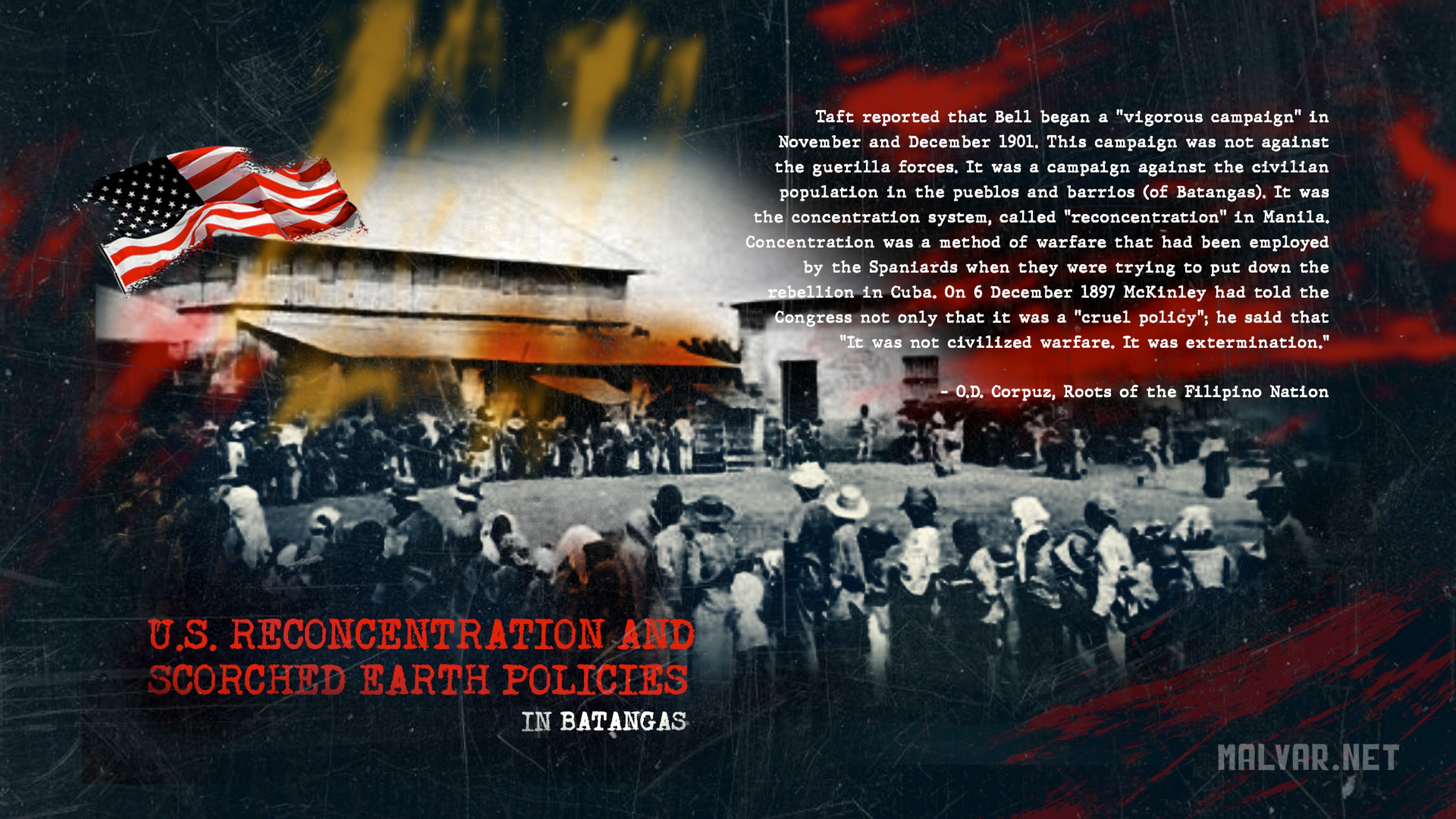

The reconcentration of Batangas was a brutal counterinsurgency campaign implemented by the U.S. Army during the Philippine-American War in 1901–1902. The policy involved forcing civilian populations into designated zones, or concentration camps, to separate them from Filipino guerrillas led by General Miguel Malvar. It resulted in thousands of civilian deaths from famine, disease, and the destruction of their homes and livelihoods. Ironically, the U.S. had condemned Spain's use of a similar reconcentration strategy in Cuba just years earlier.

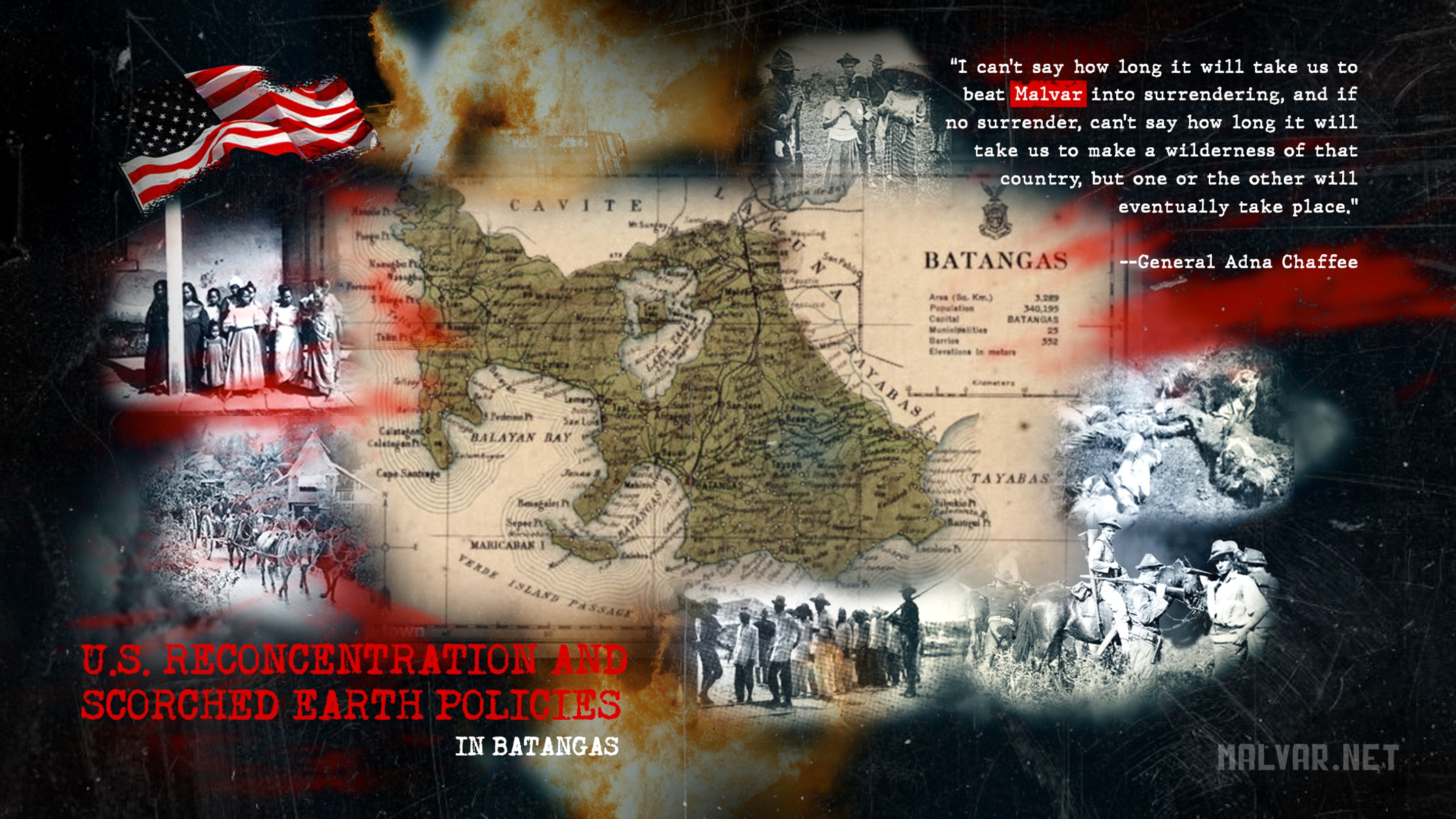

- Context: Following the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo in April 1901, the Philippine-American War was not over. Resistance, particularly in southern Luzon, continued under the leadership of General Miguel Malvar.

- Guerrilla warfare: Malvar's forces employed highly effective guerrilla tactics, which relied on the support and cooperation of the local civilian population for supplies and information.

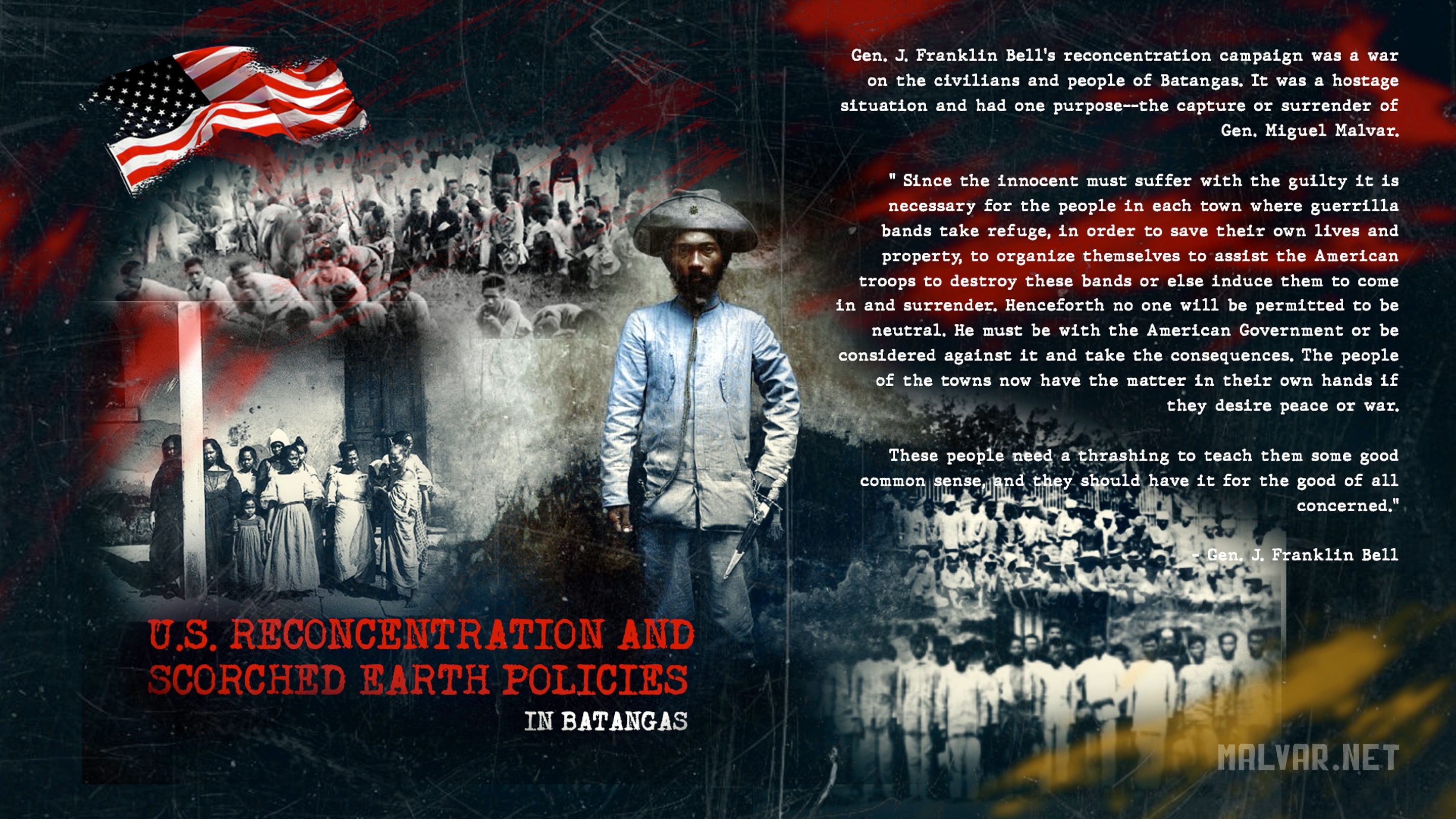

- American commander: To suppress the uprising, U.S. Army Brigadier General J. Franklin Bell was put in command of the region. He issued the reconcentration order in December 1901.

Background

- Response to guerrilla warfare: After the initial phase of the war, Filipino resistance turned to guerrilla tactics. The U.S. military found it difficult to distinguish insurgents from civilians who were providing them with support, food, and shelter.

- Separation of civilians from insurgents: The core purpose of the policy was to separate the civilian population from the guerrillas, depriving the resistance fighters of their support base. Anyone found outside the reconcentration zones was considered an enemy insurgent and subject to being arrested or shot.

- Authorized by military codes: Secretary of War Elihu Root insisted that the policy was in accordance with the U.S. Army's 1863 Lieber Code, which allowed for strict reprisals against civilians supporting insurgents, including the destruction of property and expulsion of noncombatants.

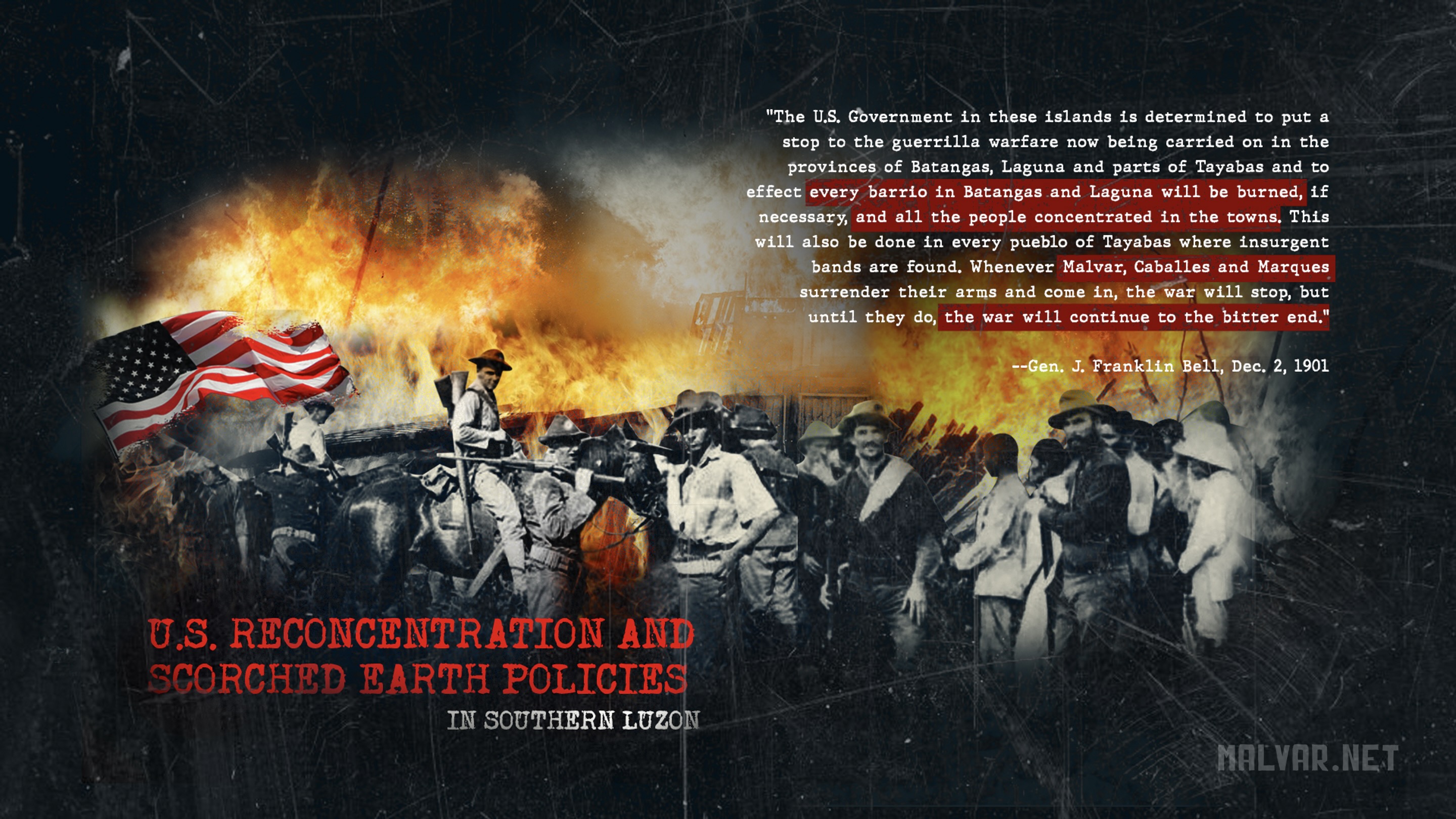

- Infamous military campaigns: The policy was most famously and brutally implemented by Brigadier General J. Franklin Bell in the provinces of Batangas and Laguna in late 1901. Bell forced tens of thousands of residents into "zones of protection," ordering the destruction of food and shelter outside these zones to starve out the resistance.

- Scorched-earth tactics: Outside the "zones," Bell ordered a campaign of complete destruction. U.S. troops destroyed homes, crops, and livestock to deprive the guerrillas of food and resources. This created a "desert waste" outside the camps.

- Forced starvation: The destruction of the surrounding countryside created famine, forcing civilians to enter the camps where food was often scarce. Bell's objective was to make the civilian population "feel the full hardship of war" to coerce them into withdrawing support for the guerrillas.

Justification and implementation

- Disease and starvation: The reconcentration zones were often overcrowded and lacked adequate food, water, and sanitation. Overcrowding led to widespread outbreaks of disease, such as cholera and measles, and the destruction of crops caused food shortages.

- High mortality rates: Historians estimate that as many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died during the Philippine-American War due to violence, disease, and starvation, much of it connected to the reconcentration policy.

- Forced labor: In some camps, able-bodied Filipinos were forced to work on roads and bridges in exchange for rations, further blurring the line between civilian and enemy treatment.

- Legacy of resentment: Though the policy helped hasten the end of organized resistance, it created long-term resentment among Filipinos. As one Filipino newspaper wrote in 1905, the measure created "feelings of animosity and rancor that will not be forgotten for many years—perhaps never".

- Official silence: Unlike the British in the Boer War, the U.S. government did not conduct a centralized investigation into the brutal conditions of its reconcentration camps. Secretary of War Root controlled the flow of information, and the fate of the Filipinos did not receive significant public attention due to the limited power of anti-imperialist opposition.

Conditions and consequences

- High death toll: The unsanitary conditions and food shortages in the overcrowded camps led to thousands of deaths from starvation and epidemics like cholera. A U.S. military study reported that between January and April 1902, 8,350 out of 298,000 people died in the camps, with some areas experiencing mortality rates as high as 20%.

- End of resistance: The campaign was effective at breaking the morale of the local population and cutting off support for the guerrillas. A lack of food and supplies forced General Malvar to surrender in April 1902, ending organized resistance in the region.

- Controversy: Critics have called the reconcentration policy a war crime. During a U.S. Senate hearing in 1902, critics highlighted the inhumane conditions and high mortality rates in the camps, despite official U.S. Army assurances that the camps were "humane".

- Historical context: The reconcentration campaign in Batangas was a brutal example of the counterinsurgency tactics used during the Philippine-American War and mirrored similar policies implemented by the Spanish in Cuba and the British in the Boer War.

Impact and legacy