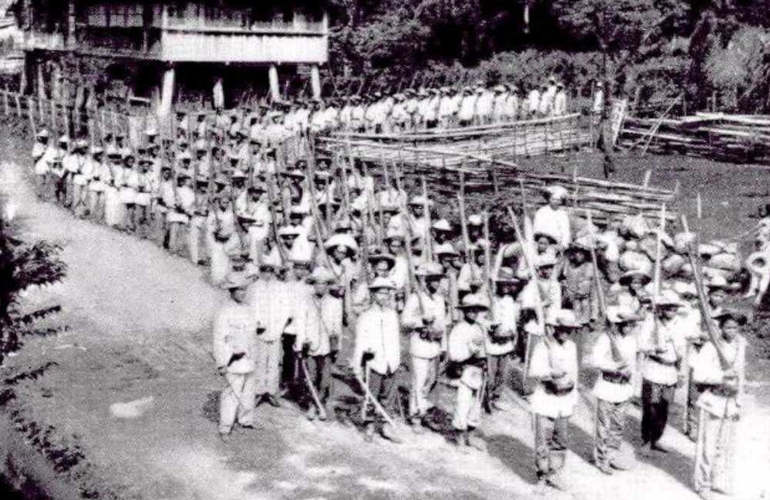

Banahaw Battalion

The Banahaw Batallion with Miguel Malvar(left of center) and Eustacio Maloles(center)

Aguinaldo's 20 July decree shows that, despite his and his generals' desire to forge their fighting forces into a regular army, the "Liberating Army" could never be a militaristic institution. According to Corpuz, "the army could never have a life apart from that of the people and the pueblos." The captains, lieutenants, sergeants, and corporals were supposed to be elected by the rank-and-file. Aguinaldo ordered that soldiers should be given leave for them to return home and tend their crops. The suggestion is that the army of the republic cannot be studied apart from the social and economic fortresses that buttressed it from above and below. Indeed, the American scholar Glenn May has argued that the southern Tagalog revolutionary army was formed out of patron-client, family, and personal ties. Malvar was allowed by Aguinaldo's decrees to choose his own corps of officers. These appointments had to be confirmed by the Secretary of War, but generally, Malvar had his way. Thus, most of his top officers were part of the local gentry who had become his fellow comrades in the sieges of Lipa, Tayabas, and other Spanish strongholds.

Glenn May lists Santiago Rillo, Arcadio Laurel of Talisay, Nicolas Gonzales of Tanauan, Melecio Bolaños of Rosario, Gregorio Catigbac of Lipa, and Cipriano Lopez of Balayan as having received appointments as lieutenant colonels in Malvar's army. What mattered most in these appointments was these officers' personal relationship to Malvar. A dozen of them or so were his classmates in the secondary school run by maestro Malabanan in Tanauan. Others were his compadres, debtors, friends, and relatives. In other words, Malvar's officers corps--in the absence of military schools and a tradition of a standing army--was nothing but his personal clientele, "responsible to and dependent on him alone." This made for a deeply flawed situation, May asserts, a collection of "private armies" whose warlord-type leaders were beholden to de facto strongman Malvar.

One problem with May's view is that it puts the southern Tagalog army of Malvar in the category of "primitive" or "pre-modern" dominated by personalistic rather than rational, institutional ties. In contrast, the U.S. Army, which clashed with the Filipino forces beginning January 1899, is portrayed by May as built along modern lines. He can thus explain that Filipino defeat in terms of negative cultural traits that led to internal divisions, rather than the overwhelming superiority of the American army and its use of ploys and tactics that had proven to be successful in the subjugation of the North Americans and Hawaiians.

A close examination of the formation of one of Malvar's military units can clarify or dispel some of May's contentions about the nature of the Filipino army. In October 1898, not long after the concentration of weapons and men after the Spanish defeat at Tayabas, the provincial forces were organized into the Tayabas Provincial Battalion, more commonly known as Banahaw Battalion (Batallón Banahaw), composed of six companies and a general staff. Malvar's hold over the battalion is evidenced in his pharmacist brother-in-law Eustacio Maloles' appointment as Colonel and over-all Jefe. But granted that kinship was important, the battalion's records refer repeatedly to Maloles' participation in armed combat, from the "first revolution" (1897) in which he played a crucial role in the liberation f Lipa, to his position as interim commander in the successful assault on the Tayabas garrison in 1898.

Next in the line-up of the battalion is Lt. Col. Buenaventura Dimaguila, aged 28, a native of Liliw, Laguna, and a "proprietario" (landlord) by profession. Then come two majors: Mariano Castillo, aged 32, of San Juan Batangas, another proprietario; and Antonio Magsino, aged 35, of Unisan, Tayabas, also a proprietario. Age, obviously, was not a factor at this level. But the "old school tie" posited by May cannot be determined here. The most we can say is that these officers were all experienced in combat, knew Malvar personally, and that their towns of origin represented the western, northern, southern, and eastern sectors, respectively, of the Banahaw Battalion's sphere of operations. The twenty-one other officers, from captain down to second lieutenant ranged in age from 22 to 35, with age 27 being the mean. The provinces of Laguna, Batangas, and Tayabas were about equally represented. Aside from a "Notario y Professor" and a "Professor y Agronomio" assigned as aides to the top brass, and two "Maestros" at the Company level, the rest are described as "proprietario."

One thing about all these officers is that they were all young and had all tasted war, most having met each other in the siege of Tayabas. Out of their fairly comfortable pasts as landowners and professionals they were now becoming "militar" and in 1899 and 1900 would face the real test of confronting the vastly superior U.S. forces, or, even worse, playing a waiting game in the malaria-infested foothills of Mt. Banahaw. On 13 December 1898, the newly installed officers of the battalion recited an oath, in Tagalog, to defend to their last breath the flag that symbolized the independence (kasarinlan) of the land of their birth. They swore to live up to the ideals of being a military officer (pagka Militar) with a "fullness of loób," and to work for the redemption of the honor (pagbabangong puri) of their country. The language of the oath cannot be treated lightly. The act of swearing before God and country simply cannot be subordinated to matters of self-or factional interest in the behavior of this elite. Their eventual surrender came at different phases of the war and one must first look for the pain and suffering before concluding that U.S. promises alone lured them out of the hills